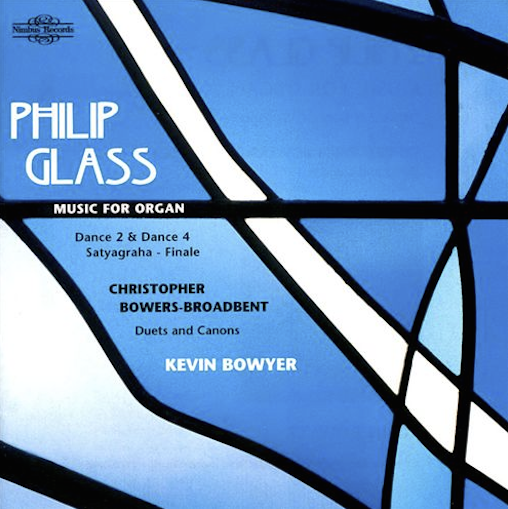

Kevin Bowyer, organ

Catalog

Tracks

1. Dance No. 2 24:45

2. Satyagraha ? Act III Finale 7:19

3. Dance No. 4 17:24

CHRISTOPHER BOWERS-BROADBENT

Duets and Canons

4. IKyrie 1:47

5. IIad Tertiam 1:02

6. IIIPuer natus 1:28

7. IVAlleluia 2:16

8. VCredo 3:05

9. VISanctus 2:30

10. VIITui sunt 2:24

11. VIIIGloria 1:48

12. IXViderunt omnes 2:21

13. XAgnus & Benedicamus 2:22

Notes

Painting is about looking, writing is about speaking and music is about listening. That’s obvious isn’t it? But it isn’t obvious.

— Philip Glass

It is now more than thirty years since the first music by Philip Glass was played in concert — to an audience of just twenty five. Inevitably, much has happened since then: critical perceptions have matured, Glass’ audience has grown vastly and he has continued to develop and compose prolifically; but the thrill of hearing that ‘early’ Glass is still vibrant.

Significantly, in that first concert, Glass performed himself. He has remained very much the composer-performer — mainly on keyboard — and it is his hands-on, almost improvisatory approach to his music that gives it that certain freshness and makes him such an exciting musician. That his music is also very carefully structured is no contradiction.

Born in 1937 Philip Glass discovered music through the unsold records that his father brought home from his radio repair shop in Baltimore; among them, sonatas by Schubert, symphonies by Shostakovich and the late Beethoven string quartets. He began the violin at the age of six, the flute at eight and at fifteen he went to Chicago, did a degree in maths and philosophy and practised piano in his spare time. From there he studied composition at the Julliard School in New York. Further studies in Paris under Nadia Boulanger and Darius Milhaud followed. It was then that he met Ravi Shankar while working on a commission from filmmaker Conrad Rooks to translate Shankar’s music (the modal scales and extended rhythmic cycles of Hindustani classical music) into Western notation. This was to have the most profound on Glass: “With Ravi, the composer and performer became one person. In 1965 I was trying to figure out how I was going to make my way in the music world and it was inspiring seeing that there were people who were performers and composers in the same person”.

It was also at this time that his ideas of collaboration with other artists were taking shape. Glass became fascinated by the sheer range of an artist such as Cocteau; here was a man who wrote poetry, screen-plays and music as well as directing films, opera and theatre works in collaboration with composers such as Stravinsky, Satie, Poulenc and Milhaud. Glass recalls talking to Darius Milhaud in 1960 about artistic life in Paris forty years earlier: “Artists, dancers, writers and composers working together was an idea fully explored at that time. I guess the war pretty, much put an end to it”. Later, it was Glass’ ground-breaking collaboration with director Robert Wilson in Einstein on the Beach (premiered in 1976 and now seen as a landmark in 20th century music theatre) that established the now New York resident composer as one who positively delighted in collaboration as a means of pushing the limits of performance art: “Authorship has become something that is not simply the point of view of one self-centred ego maniac composer. That’s not the way one works these days”.

By 1974 Glass had composed a large collection of new music, much of it for use by the theatre company Mabou Mines of which Glass was a co-founder and most of it composed for his own performing group, the Philip Glass Ensemble. Dance 2 and Dance 4 are the two solo organ movements of a five-part dance work created in the early 1970s in collaboration with the choreographer Lucinda Childs and the visual artist Sol Lewitt.

So far I have avoided the word ‘minimalism’ but because Glass’ music repeats, varies and builds on only a few musical ideas the term minimalism began to be applied to it. Glass says: “Minimalism supposedly tells us something, but in fact it obscures more than it reveals. It is soundbites, whereas really the difference between us composers who were known as minimalists are much more interesting than the similarities”. Glass is sometimes thought to have invented minimalism but, as he admits: “It was in the air. It was bound to happen”. This spare, almost anorexic music puzzles some people, fascinates others. A typical audience reaction to Glass’ music in the 1970s and 1980s included frantic ‘bravos’ and violent ‘boos’, sometimes paradoxically coming from the same people; traditionalists deplored the lack of narrative progression. Today we can thankfully see the much wider picture. The constant beat and yet subtly shifting rhythmic cycles over a seemingly static harmonic structure gives the listener a heightened sense of time and, instead of long development sections, progression is achieved through the increasingly complex repetitions and overlapping lines.

It is not surprising, however, that Philip Glass has achieved his greatest success in the field of opera; for this is the art form which is essentially a collaboration. Indeed, it is not too extreme to say that he can be credited with the very revitalisation of opera during the last quarter of the 20th century. Robert Jones has written: “The half century between Puccini’s Turandot (1926) and Glass’ Einstein on the Beach (1976) were distinguished by an increasing complexity in music to the point where new music of any kind became identified in the public’s mind with ugliness and incomprehensibility. Occasionally an opera company would produce something new, but it invariable failed to attract a public and the production of new operas became anathema to opera companies. Satyagraha (1980) changed all that. As one theatre piece after another emerged from Glass’ studio, the opera world sat up and took notice”.

The Finale is a piece transcribed and edited by Michael Riesman, Glass’ long-time collaborator, from the Act Three conclusion of Satyagraha; a ‘portrait opera’ on the life of Gandhi and one of a trilogy of large-scale portrait operas which included Einstein on the Beach and Akhnaten (1984).

— Christopher Bowers-Broadbent, 2000

NOTES ABOUT KEVIN BOWYER

Kevin Bowyer was born in Southend-on-Sea in January 1961. He studied with Christopher Bowers-Broadbent, David Sanger and Virginia Black and has won first prizes at the international organ competitions in St. Albans, Dublin, Paisley, Odense and Calgary. He has played throughout Europe, North America, Australia and Japan and has become celebrated for contemporary and unusual repertoire. He has broadcast widely for the BBC and many radio stations throughout the world and has released more than fifty recordings. His legendary sense of humour, which makes him popular with audiences, has also made him a highly sought after teacher; in which capacity he works at the St. Giles International Organ School in London, Warwick, Oxford and Leicester and at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester.

Kevin also reads (in particular Joyce, Beckett and the Powys family), drinks (real ale and malt whiskies) and enjoys the odd pinch of snuff.

Credits

Performed by Kevin Bowyer at the Marcussen Organ at Tonbridge School, Kent.

Produced by Dominic Fyfe.

Recorded in the Chapel of St. Augustine, Tonbridge School, Kent. June 1st & 2nd 1999.

Designed by Chloë Rafferty. Photographs © Sonia Halliday Photographs.

© 2001 Nimbus Records Limited.

Buy

Related

Dance Nos. 1-5

Satyagraha

RECORDINGS:

Dance Nos. 1-5 on Sony Masterworks

Satyagraha on Sony Masterworks