Bruce Levingston, piano

Catalog

Tracks

A Musical Portrait of Chuck Close

1. Movement I 4:19

2. Movement II 7:48

MAURICE RAVEL

3. La vallée des cloches 7:02

4. Alborada del gracioso 7:31

OLIVIER MESSIAEN

5. L’échange 4:41

6. Regard de la Vierge 9:10

7. L’Alouette Lulu 9:54

ERIK SATIE

8. Sarabande No. 2 5:24

9. Gnossienne No. 4 2:34

10. Gymnopedie No. 1 3:52

Notes

The idea for A Musical Portrait of Chuck Close occurred to me just before I played a concert in The Rockefeller University’s Caspary Hall. Outside the hall’s foyer hangs one of artist Chuck Close’s iconic renderings of Philip Glass. As I looked at it, I kept thinking about how Chopin and Liszt had been drawn and painted by the great artists of their day such as Delacroix and Ingres and also how many of the Romantic composers had in turn brilliantly portrayed their friends and contemporaries through their music. I thought, “Glass has to compose a portrait of Close.” About a month later, a fortuitous meeting occurred. I met both Chuck Close and Philip Glass at a reception in New York. I immediately told Glass about seeing his portrait at the hall and my idea for a portrait of Close. He seemed genuinely moved and immediately accepted the project.

The printed score of A Musical Portrait of Chuck Close arrived electronically in September 2004. I’ll never forget the thrill of taking each page off the printer and running to the piano to see what the piece would feel like under my fingers. Each passage brought new and wondrous sounds and ideas. On April 25, 2005, I premiered the work at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall in New York City. It was a memorable evening that celebrated not only great music and art, but also great friendships, and the important and lasting influences they have on the creative process.

When I set out to create a disc of music that would complement the new Glass work, I sought pieces that shared not only representational qualities, but also certain communicative and emotional characteristics. The Messiaen, Ravel and Satie pieces all possess these expressive traits. While artistically quite unique, each of these works nonetheless resonates with the other. They share a kinship with the Glass work, not only in their musical and historical ties, but also in the power and subtlety of their expression.

— Bruce Levingston

January 2006

PHILIP GLASS

A Musical Portrait of Chuck Close

(world première recording)

Philip Glass is one of the most important artists of our time. He has composed for dance, film, opera, orchestra, and theater. His 1976 operatic collaboration with Robert Wilson, Einstein on the Beach, is considered a landmark in twentieth century music-theater. Born on January 31, 1937, Glass graduated from the University of Chicago at age 19 with degrees in mathematics and philosophy and then studied at The Juilliard School with Vincent Persichetti and in Paris with Nadia Boulanger. While in Paris, he was hired to transcribe the music of Ravi Shankar and discovered the techniques of Indian music. After researching music in North Africa, India and the Himalayas, Glass began applying Eastern techniques to his own work. This eventually led to a musical breakthrough using a style that came to be called Minimalism.

Although Glass never claims to have invented Minimalism and maintains the form only applies to his earlier compositions, his is the name most associated with the movement. Glass has said of that era and the movement: “It was in the air. It was bound to happen.” Certainly his earliest music lacks the traditional sense of narrative progression typically associated with classical music. There is also a sense of harmonic repetition and lack of thematic development linked to Minimalism. However, in recent years Glass’s works have evolved in both musical complexity and structure that can now hardly be called minimal. While certain principles remain constant such as maintaining a sparse number of harmonic and developmental changes, Glass utilizes greater rhythmic and thematic variations to evoke deeper fields of sound and emotion.

Chuck Close and Philip Glass

This evolved style can be heard in Glass’s A Musical Portrait of Chuck Close. Composed as a diptych in two harmonically related but distinctly different movements, this work is a spiritual reflection of Chuck Close, and a tribute to the friendship between two of the most influential artists of their generation. Close and Glass first became friends in the late 1960s when both worked as assistants to the sculptor Richard Serra. Close was then taking photographs and painting images of his friends. He specifically did not want to paint “famous” people although many of his subjects, including Glass, Serra, Roy Lichtenstein, Alex Katz and Robert Rauschenberg, did ironically become famous in their own right. Close called his portraits “heads” to emphasize they were exercises in “form not biography.” Unlike traditional portraits, Close’s “heads” gave every aspect of an image equal value and importance.

The most best known of these “heads” is undoubtedly that of Philip Glass. Poor Phil, “Close said in a 2005 interview with Charles McGrath of The New York Times. “I’m still using that same old photograph. Every time I go back I see something different. It’s like going back to a magic well.” Close said what appealed to him about that early photograph were Glass’s “curly, dendritic locks” which reminded him of Medusa. The portraits are, Close admits, “a kind of accidental record of a friendship.”

Glass’s A Musical Portrait of Chuck Close, while not depictive in a literal sense, offers yet another record of that friendship. “What the musical portrait and Mr. Close’s paintings have in common,” McGrath wrote, “is a method and a philosophy —a kind of minimalism, though that’s not a term that either man cares much for. Both artists work with very small elements, “bricks” Mr. Close sometimes calls them, discrete bits of information that are repeated and carefully varied to create a whole.”

“If you look at some of Chuck’s paintings, they’re modules that are put together and shaded with different values,” Glass said. “And I’ve used that idea with modular music also. But there’s another aspect of it which is perhaps more important, which is that his work is really about creating art out of an exhaustive and detailed process, so that the entirety of the work is a reflection of the integrity of the process. One of the things that was very interesting for us as a generation was to replace the narrative of painting and the narrative of music with a different kind of balance.”

According to Glass, his musical portrait is less a matter of conscious reflection than of shared experience. “I’ve known Chuck very well and over a long period of time. I knew him when he got married and when he had children and when he had the illness and when the children went away to college. I was married to a painter who died some years ago, and after she died he came to the house and —with some effort, he was in the wheelchair then— we looked at her work together and he advised me what to do with it and so forth. And so we’ve been, I think —to copy a word he said— we’ve been embedded in each other’s lives.”

A Musical Portrait of Chuck Close

In 1988, Close’s life was dramatically bisected and altered by a spinal aneurism that both limited and eventually liberated his work. After a wrenching struggle with the physical limitations brought about by his illness, Close taught himself to paint again with brushes strapped to his arms. Close has described the before-and-after emotions of his losing and regaining the ability to make art as “loss and celebration.” The works following Close’s recovery became freer and more colorfully expressive than ever before. The two movements of Glass’s portrait vividly portray the life and soul of this extraordinary artist, first in the assuredness and virtuosity of his youth, and then in the bittersweet, transcendent mastery of his maturity.

The brightly colored, highly kinetic first movement opens with a bewitching six-against-four rhythmic figuration that playfully alternates between major and minor while vibrant chords jubilantly ring out in the treble and bass. Luminous, cascading scales emerge from these figurations, first in the left hand, then in the right, and finally with both hands playing together in descending and ascending contrary motion. In the midst of all this, two disquieting bi-tonal passages briefly foreshadow darker things to come. The movement ends nonetheless with a gentle recapitulation of the opening figurations that resolve, at the last possible moment, into a momentary calm and peaceful F major sonority.

The second movement, cast in D minor (the relative minor key of F major) opens with a restless, undulating figure in the left hand. A simple broken chord repeatedly rises up above this accompaniment in a counter-rhythm while slight chromatic variations gently bend the top line to and fro. A new descending theme makes its entrance in graceful counterpoint to the ascending broken figure. As the music unfolds, multiple layers of dynamic, rhythmic, and thematic variation build in complexity and intensity. A surge of raw emotion finally erupts with a torrent of arpeggios that swirl over a throbbing left-hand ostinato. In the midst of these waves of sound, the descending theme is heard once again, this time subtly woven within the arpeggios. As this climactic moment subsides, the opening, undulating figure of the left hand can once more be heard. The arpeggios then solidify into softly pulsating chords that repeat themselves in subtle harmonic progressions. As these chords begin to fade, echoes of the swirling figures return with a re-emergence of the opening and counter-themes, each quietly alternating with the other. Four wistful, arpeggiated chords beckon through the return of the gently rocking figuration, which seems to resonate, even after its whispered close. “To me,” Glass reflected, “the second piece has an expansiveness to it, it just seems to keep going on and on. And it’s like trying to find the edge of the canvas in one of Chuck’s paintings. There’s an edge there because there has to be an edge somewhere. But in another way you could say, well, why doesn’t it keep going forever?”

MAURICE RAVEL (1875-1937)

La vallée des cloches

Alborada del gracioso

(from Miroirs)

Ravel wrote that his Miroirs “marked a rather considerable change in my harmonic evolution.” This “change” no doubt refers to the use of many unresolved chords played over long pedal points as well as developed by Erik Satie.

An exquisite evocation of Parisian church bells, La vallée des cloches (The valley of bells) clearly shows the influence of Satie, particularly his Sarabande No. 2, which is dedicated to Ravel. The repeating tones of the bells, as well as the mystical figurations of the opening and closing measures, seem to anticipate the textural and temporal techniques of the Minimalists.

Alborada del gracioso (Aubade of the jester) is exactly what its title suggests. An aubade is a poem or song of or about lovers separating at dawn, and gracioso is the clown or “fool” of Spanish comedy. Combining these two ideas with humorous, biting harmonies, sharp accents, and guitar-like repeated notes, Ravel paints a brilliant and sensual portrayal of a lover’s mischief and passion. The work is a pianistic tour de force that reflects the composer’s life-long fascination with Spanish art and culture.

OLIVIER MESSIAEN (1908-1992)

L’échange

Regard de la Vierge

(from Vingt Regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus)

Inspired by a deep theological conviction in Catholicism and a profound love and adoration of nature, the music of Messiaen expresses a powerful vision of religious symbolism and mysticism. The sublime Vingt Regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus (Twenty Contemplations upon the Infant Jesus) is the apotheosis of the spiritually inspired music of this modern French master. In his vast and deeply expressive work, Messiaen depicts not only the figures in Christ’s life but also physical and spiritual events from His birth to death to resurrection. The entire cycle is filled with symbolism: themes that represent God, the cross, the star; chords that represent the Virgin, the prophets, the shepherds and the magi; and, of course, Messiaen’s beloved birdsong, which represent the songs of the angels.

L’échange (The exchange) represents, in Messiaen’s own words, “the terrible trade of the human-divine… God becomes man to give us back God.” L’échange is thus a portrait of both God and man. Messiaen constructs this dramatic and extreme “soundscape” by allowing certain figures to remain unchanged; these represent the divine; others change asymmetrically, and, as Peter Hill notes: “in these, certain pitches rise, others fall or, exceptionally, remain static, so that the effect is of shapes that recoil and reform.”

In his preface to Regard de la Vierge (Look of the Virgin), Messiaen writes:

Innocence and tenderness…woman of purity, the wife of the Magnificat, the Virgin looks upon her Child…

I wanted to express purity in music: a certain power was necessary —and above all much naïveté, of pure tenderness.

One of the most intimate and touching movements in the entire cycle, Regard de la Vierge portrays not only the love and compassion of the Mother for her Son, but also her glimpses of the violence and death she would witness at the end of His life. This exquisite work, replete with the celebratory sounds of bells and birdsong, is one of the composer’s most personal utterances.

L’Alouette Lulu

(from Catalogue d’Oiseaux)

In his immense Catalogue d’Oiseaux (Catalogue of Birds), the composer’s love for God and nature finds an ideal synergy. Each of the catalogue’s thirteen works brilliantly depicts various forms of bird-life. By transcribing rhythms and pitches of actual birdsong, Messiaen not only portrays individual species but also, through his ingenious harmonic coloring, their hours of activity, natural habitat and geographical location.

L’Alouette Lulu is an evocation of the nocturnal woodlark. Deep organ-like chords (marked la nuit in the score) represent the night while shimmering, chromatic figurations (marked poètique, liquide, irréelle) depict the song and flight of the woodlark. A nightingale also makes an appearance that the composer notes in the score: “La voix de la terre (Rossignol) répond a la voix du ciel (Alouette Lulu) [The voice of the earth (Nightingale) responds to the voice of heaven (Woodlark)]. The nightingale has long represented earthly love in music. The two different species symbolize for Messiaen the body and the spirit, the profane and the sacred, and a prayerful communing of man with his God.

ERIK SATIE (1866-1925)

Sarabande No. 2

Gnossienne No. 4

Gymnopédie No. 1

Erik Satie was one of the most influential yet misunderstood composers in music history. Thought once only to have been the composer of light and droll works, he actually wrote pieces that changed the course of music history. Debussy and Ravel both acknowledged their tremendous debt to the eccentric French genius. Ravel publicly performed the second Sarabande with its grave yet luxuriously unresolved ninth chords, while Debussy, who called Satie a gentle medieval musician, orchestrated the first and third Gymnopédies.

The Sarabandes, Satie’s first important piano works, were written in 1887. A slow and stately dance, the Sarabande of Satie, no less noble than its eighteenth century models, is colored by exquisite textures and mysterious harmonies undreamt of by preceding composers. Also reminiscent of an earlier age, the tender, piquant phrases and modal figurations of the Gnossienne and Gymnopédie (titles made up by the composer with vague Grecian allusions) suggest the graceful arabesques of ancient Greek dancers.

These quiet and touching works of Satie, while not overtly pictorial, are delicately evocative of human movement and dance. Their subtle tone and structure, so influential to generations of composers, belie their true depth of feeling and emotion. Like the music of Glass, Ravel and Messiaen, each expresses aspects of earthly and spiritual life. And all these works, grounded in nature, people, places, and friendship, express simple but powerful aspects of the human experience.

— Notes by Bruce Levingston

Credits

Producer: Bruce Levingston. Piano technician: Ed Wedberg. Steinway piano.

Engineer: Tom Lazarus. Recorded in July and August 2005; Caspary Hall, The Rockefeller University, New York City.

Special thanks to: Chuck Close; Jo Ann Corkran and Randolpho Ezratty; Philip Glass, Dunvagen Inc.; Peter Goodrich, Steinway and Sons; Augusta Gross and Leslie Samuels; Agnes Gund and Daniel Shapiro; Tom Lazarus and Bart Migal, Classic Sound; Charles McGrath; Daniel Nuxoll; Pace Prints, Inc.; Premiere Commission, Inc.; Beckley Roberts Design; David Rockefeller; The Rockefeller University; Michael Volchok, Volchok Consulting, Inc.

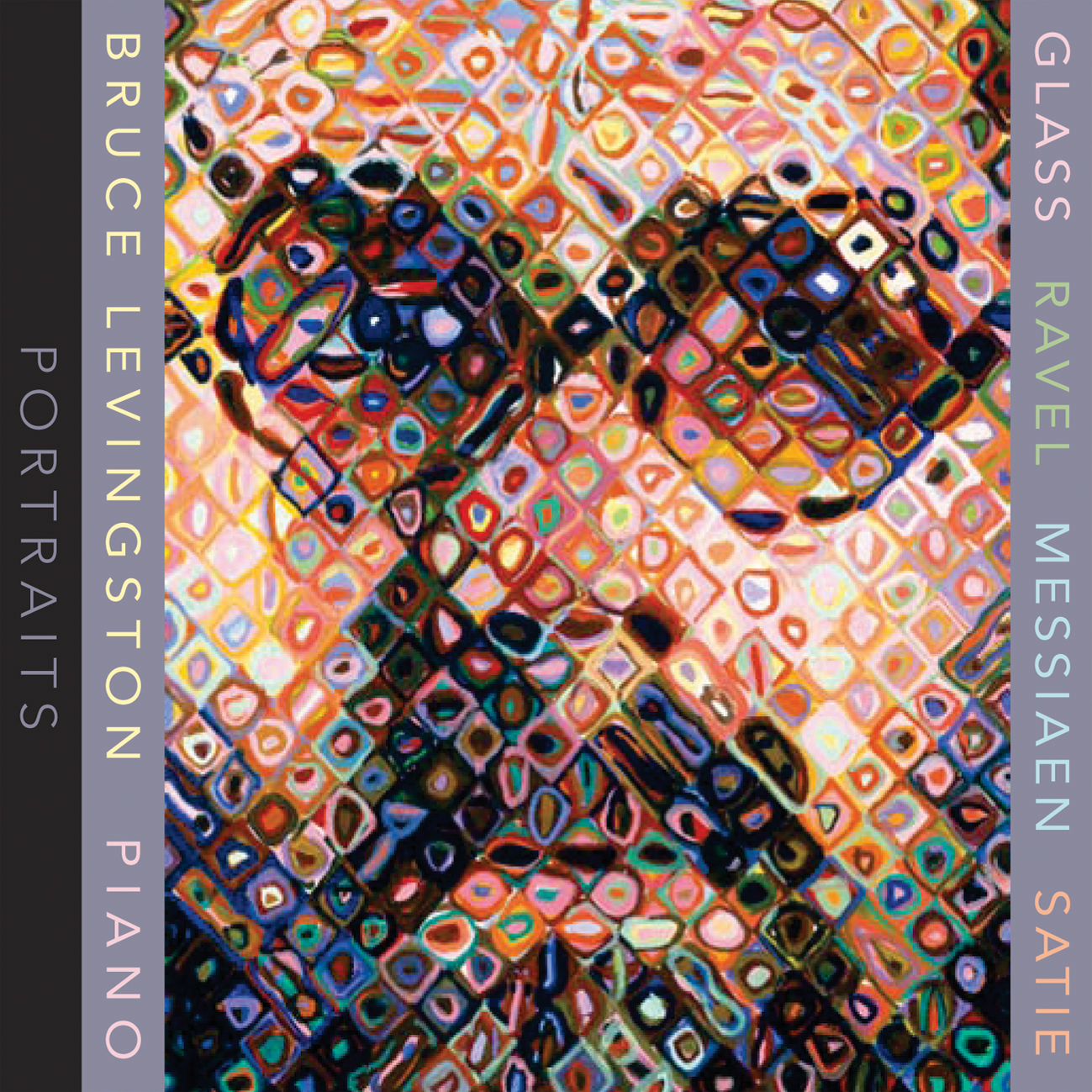

Cover: Chuck Close; Self Portrait, 2002; 43-color hand printed woodcut on Nishinouchi paper. Published by Pace Editions, Inc.

Philip Glass’s music is published by Dunvagen Music Publishers, Inc. (ASCAP).

℗ and © 2006 by Orange Mountain Music.