Steffen Schleiermacher, electric organ, table

Catalog

Tracks

One+One (1st version) 5:25

Mad Rush 14:27

One+One (2nd version) 2:30

Two Pages 27:25

Notes

In contrast to his later great compositions for music theater, which usually come across as quite pleasing and varied, these early pieces by Glass seem quite archaic in their uniform coloration and monotony. They show us minimalism, so to speak, in statu nascendi.

Together with LaMonte Young, Steve Reich, and Terry Riley, Philip Glass belongs to the co-founders of minimal music.

Who may have influenced whom among these composers, who discovered what for himself, what differences there are in their individual approaches to sound, how the mutual influence from artists representing minimal art like Frank Stella, Donald Judd, or Sol LeWit may have worked in concrete terms will have to be left open here. Suffice it to say, that the four composers have in common a turning away from the European tradition of music (which at least Glass and Reich, as pupils of composers like Darius Milhaud, Nadia Boulanger, and Luciano Berio, new very well) and a turning to music from outside Europe, which in the 1960s as a rule was understood as Indian music.

Although Glass also knew some Moroccan or Central African music (with the latter also having been very important for Steve Reich), he was especially fascinated by Indian music or, more precisely, Northern Indian art music, with which he became more closely acquainted through his contact with Ravi Shankar and Alia Rakha. Just as Reich traveled to Ghana to study drum music, so too Glass (as well as LaMonte Young and Terry Riley) traveled to India to occupy himself more intensively with the Indian tradition.

Philip Glass was never interested in copying Indian music or in composing music that would sound like a blending of European and Indian music. In fact, he even admitted that the essential thing about Indian music, namely its microintervals, remained foreign to him. Rather, what interested him was the rhythmic structure and the whole metrical system of Indian music. In contrast to the European tradition, the Indian musician does not divide a set time value into smaller values (fourth notes, eighth notes, triplets, etc.) but proceeds from a very short rhythmic value, which can be added to at will and thus produce longer values.

Glass transferred his additive procedure (actually a purely rhythmical procedure) to melodic cells which can be augmented or diminished in keeping with what are sometimes very simple rules. The smallest rhythmical value is usually the eighth note; it continues to pulse throughout, with the melodic phrases being varied additively during the course of the piece. It is thus entirely possible that by way of Indian music Glass discovered and studied such procedures in works by Igor Stravinsky. In this connection it is interesting to note that the hypnotic power so very much a part of the litany-like, almost manic effect of the repetitions in the same flowing rhythmic pace and almost typical of the whole of minimal music is foreign both to Indian music and to Stravinsky’s music.

The additive procedure in Two Pages can be followed as if in a teaching manual. The title refers to the fact that the score consists of two pages. Each measure is supposed to be repeated twenty times.

The principle of Contrary Motion is basically the same, but here a mirror part (a sort of elemental counterpoint?) and a pedal part constantly shifting between two bourdon tones are added. Since the individual phrases continue to increase in length, the alternation between these two bass tones becomes slower and slower over the course of the piece, so much so that it produces a slow-motion effect. For their part, the two upper voices always continue unwaveringly in the same tempo.

Both pieces are open works of art. The ending of the pieces is arbitrary; they break off more so than produce an actual finale effect. In fact, they could go on forever. In Two Pages countless other models would be possible within the given compositional framework, and the figurations in Contrary Motion could go on forever, becoming longer and longer. But perhaps it is precisely the sudden breaking off that brings about that mysterious feeling of endlessness.

One + One is a set of instructions for the constructing and independent testing of the additive principle. Two basic rhythmic cells are given as well as the instruction to choose a fast basic tempo and to beat out the whole on a tabletop. (Is this how Glass passed the time while he had to spend his days earning his living as a taxi driver?)

But Glass sets substantial limits to the arbitrariness of the interpreter and “co-composer” by requiring the combination of the two elements in continuous regular arithmetical progression. The rule or law invented and employed is left up to the interpreter, but one is required to invent such a rule and then to abide by it!

Mad Rush was composed as music for the first public appearance of the Dalai Lama in New York. It must have been thought of as a sort of processional music.

It consists of three clearly distinguished parts related to the same basic harmonic model but very different in their sound effect because of the registers and the figuration.

Originally the piece must have been intended as an open form as much as the parts are repeated in different order, but Glass later added a conclusion to them.

This too can be interpreted as a sign that he has abandoned the radical nonnarrative, undramatic approaches of his early period.

— Steffen Schleiermacher

NOTES ABOUT Steffen Schleiermacher

Steffen Schleiermacher, born in Halle in 1960, studied piano (Gerhard Erber), composition (Siegfried Thiele, Friedrich Schenker), and conducting (Günter Blumhagen) at the Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy Academy of Music in Leipzig during 1980-85. He was an assistant in composition, ear training, and new music in Leipzig until 1988 and a master pupil under Friedrich Goldmann (composition) at the Academy of Arts in Berlin during 1986/87 and at the Cologne Academy of Music under Aloys Kontarsky (piano) during 1989/90.

Schleiermacher has been a freelance composer and pianist since 1988. As a pianist he focuses exclusively on music of the twentieth century. He has concertized as a soloist with the Gewandhaus Orchestra of Leipzig, Munich Philharmonic Orchestra, German Symphony Orchestra of Berlin, Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, and other orchestras under Vladimir Ashkenazy, Friedrich Goldmann, Ingo Metzmacher, Jörg-Peter Weigle, Wladimir Siwa, Vladimir Fedosejev, and Fabio Luisi. Concert tours have taken him throughout numerous European, South American, and Far Eastern countries.

During 1984-88 he directed the Gruppe Junge Musik at the Leipzig Academy, and in 1989 he founded the Ensemble Avantgarde. He has presented the Musica Nova series at the Leipzig Gewandhaus since 1989 and has led the January Festival at the Museum of the Plastic Arts in Leipzig since 1991.

Schleiermacher’s numerous prizes and fellowship awards include the Gaudeamus Competition (1985), Kranichstein Music Prize (1986), Hanns Eisler Prize of the East German Radio for his Concerto for Viola and Chamber Ensemble (1989), Christian and Stefan Kaske Foundation Prize, Munich (1991), Mendelssohn Fellowship of the East German Ministry of Culture (1988), German Music Council Fellowship (1989/90), Fellowship of the Kulturfond Foundation (1992-94, 1997), Fellowship of the German Academy at the Villa Massimo in Rome (1992), Japan Foundation Fellowship (1997) for study for several months in Japan, and Fellowship of the Cité des Arts in Paris.

Credits

Production: Werner Dabringhaus, Reimund Grimm. Tonmeister: Friedrich Wilhelm Rödding. Recording: March, 22, 2000, Detmold.

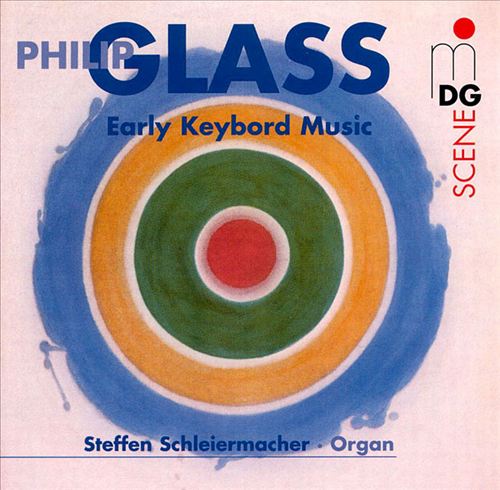

Cover: Kenneth Noland: Provence 1960.

Foto: Sabine Golde. © Text: Steffen Schleiermacher. Editor: Dr. Irmlind Capelle.

© 2001, MDG (Musikproduktion Dabringhaus und Grimm oHG), Made in Germany.

Buy

Related

1+1

Mad Rush

Music in Contrary Motion

Two Pages

RECORDINGS:

Solo Piano on Sony Masterworks

Two Pages / Contrary Motion / Music In Fifths / Music In Similar Motion on Nonesuch