info

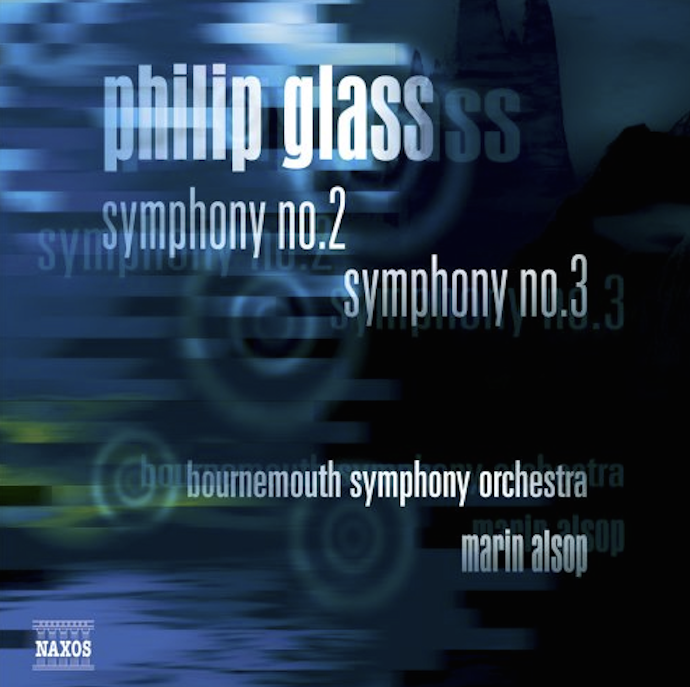

Performed by Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra

Marin Alsop, Conductor

Catalog

Tracks

1. I. 4:27

2. II. 6:17

3. III. 9:38

4. IV. 3:32

SYMPHONY NO. 2

5. I. 16:42

6. II. 13:23

7. III. 13:08

Notes

Born in Baltimore in January, 1937, Glass became familiar with music through his father, who was a radio repairman and record salesman. After attending the University of Chicago, where he studied mathematics, with music as his principal distraction, he went to New York to study at the Juilliard School. There he was extremely prolific, though he was writing music that is nothing like the work we know him for today. Like all good composers of his generation, he went to Paris to study with Nadia Boulanger, the twentieth century’s greatest teacher, but it was not through her tutelage that the apocryphal scales would fall from his eyes, but through a fortuitous work-for-hire job he got transcribing and notating Indian music played by Ravi Shankar. He withdrew all his earlier work, and began to use these Eastern techniques in his experimental music.

Glass formed his own, self-named ensemble – his approach was, and has always been, very D.I.Y. – and wrote long, repetitive process pieces for them, the most famous of them being Music in Twelve Parts (an evening length concert work) and Einstein on the Beach (a full-scale opera, and his first collaboration with director and co-visionary Robert Wilson). These stillinfluential works serve as a pair of musical “shots heard ‘round the world” for many members of New York’s downtown experimental set. As he eschewed the usual concert music venues, playing, instead, in the lofts, art galleries and clubs which populated pre-commercial SoHo and TriBeCa in the mid-1970s, his reputation, both as saint and blasphemer (depending on who you asked) grew.

The Philip Glass Ensemble continues to tour regularly with many of the same members, and though he has written much music for them, a large portion of his output continues to be for more traditional groups: there are string quartets, concertos, tone poems, film scores, operas, and symphonies. And lately his bad reviews have turned good (proving the notion that to get good notices in the New York press, one only need persevere long enough). He continues, at this date, to be as prolific as ever.

The Second Symphony was originally commissioned by the Brooklyn Academy of Music, and its première took place in 1994 there, with Dennis Russell Davies (a staunch Glass advocate, commissioning most of his orchestral music) conducting the Brooklyn Philharmonic orchestra. It is cast in three movements, large paragraphs (as Glass is wont to do), more invested in polytonality, where music is in more than one key simultaneously, than many of his other more straightforward pieces, with the exception of his big opera Akhnahten. “The great experiments in polytonality carried out in the 1930s and 1940s show that there’s still a lot of work to be done in that area,” says Glass, but, unlike the major experimenters with this sort of sound world (most notably French composers like Honegger and Milhaud) who just sort of shoved one key atop another to make for rather crunchy harmonies, dissonances that bend the ear yet still have all the benefits of normal tonal motion, form, and cadence, Glass is more interested in the ambiguity this sort of language creates. It is the aural equivalent of looking at an Escher print – you hear things differently depending on where you choose to focus your ear.

The first movement is something of a slow burn, building in intensity, dank and a little screechier than many of Glass’s “prettier” works, but ending in a calculated whimper; the second movement picks up where the first left off, equally dark, with a persistence and a sombre quality which one might hear as somewhat despondent; the final movement, contra all the fascinating murk of the preceding two, is spirited and bright, favoured by bells and whooshing woodwinds, all swirling to a barnburning conclusion.

Though it bears the same title, Glass’s Third Symphony is quite a different experience from the second. This piece, composed on a smaller scale, was commissioned by the Würth Foundation for the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra, who gave the first performance in Künzelsau, Germany, in February, 1995. When writing for a chamber orchestra, nineteen string players in this instance, it becomes less about orchestral texture and timbre, more about soloistic playing, with each instrumentalist functioning more like a member of a string trio or quartet than of an orchestra. With this in mind, Glass composed a much denser, more intimate piece, cast this time in the traditional symphonic four movements.

“The opening movement,” writes Glass (in liner notes to a prior recording), “a quiet, moderately paced piece, functions as a prelude to movements two and three, which are the main body of the symphony. The second movement mode of fast-moving compound meters explores the textures from unison to multiharmonic writing for the whole ensemble. It ends when it moves without transition to a new closing theme, mixing a melody and pizzicato [plucked strings as opposed to being bowed] writing. The third movement is in the form of a chaconne, a repeated harmony sequence. It begins with all three celli and four violas, and with each repetition new voices are added until, in the final variation, all nineteen players have been woven into the music. The fourth movement, a short finale, returns to the closing theme of the second movement, which quickly re-integrates the compound meters from earlier in that movement. A new closing theme is introduced to bring the Symphony to its conclusion.”

In both of these pieces, Glass returns (in his way) to his Juilliard roots, writing polyharmonies, rousing finales, and fully formed symphonic sprawls which are far more redolent of, say, the Vincent Persichettis or the William Schumans of his graduate school training than the Laurie Andersons or Terry Rileys of the SoHo 70s. These symphonies, though longish in duration, are taut, constructed works, bearing their name not out of flash but rather out of design. He did not just compose big pieces for orchestra and attach a classy title, for these pieces truly are symphonies in their scope, intention, and seriousness of purpose.

– Daniel Felsenfeld