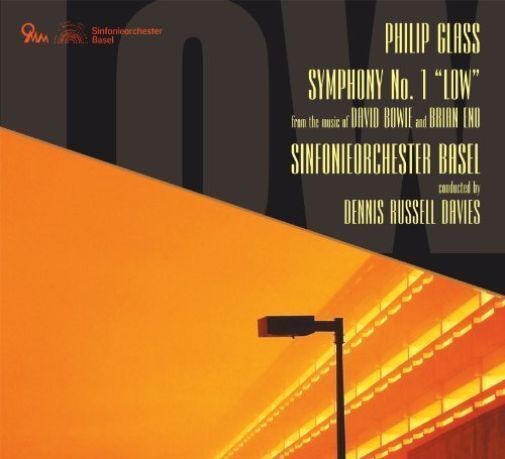

Sinfonieorchester Basel

Dennis Russell Davies, conductor

Catalog

UPC 801837009521

Tracks

2. Movement II – Some Are 11:12

3. Movement III – Warsawa 19:25

Notes

In January 1992 Philip Glass turned 55 years old. It was at this time that Glass received a commission from the Brooklyn Philharmonic Orchestra and its principal conductor Dennis Russell Davies for what turned out to be Glass’ first symphony. Glass tells the story of Davies, at that point in Glass’ career of “not letting him be one of those opera composers who never writes a symphony.” The Symphony was composed in 1992 and scored for full orchestra with 2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, percussion, harp, piano and strings. The piece is in three movements: I. Subterraneans, II. Some Are, and III. Warszawa. Glass selected these three original sources for the Symphony, varying only slightly by using a track, “Some Are” that was not on the original “Low” recording, rather it was a bonus track on the 1991 Rykodisc reissue of the Bowie Low album. The first recording of the Glass work was released in 1993 under the title Low Symphony. It was performed by the commissioner, the Brooklyn Philharmonic orchestra under the baton of Dennis Russell Davies.

In Glass’ statement in 1992 he says, “The “Low” Symphony, composed in the Spring of 1992, is based on the record “Low” by David Bowie and Brian Eno first released in 1977. The record consisted of a number of songs and instrumentals and used techniques which were similar to procedures used by composers working in new and experimental music. As such, this record was widely appreciated by musicians working both in the field of “pop” music and in experimental music and was a landmark work of that period. I’ve taken themes from three of the instrumentals on the record and, combining them with material of my own, have used them as the basis of three movements of the Symphony. Movement one comes from “Subterraneans,” movement two from “Some Are” and movement three from “Warszawa.” My approach was to treat the themes very much as if they were my own and allow their transformations to follow my own compositional bent when possible. In practice, however, Bowie and Eno’s music certainly influenced how I worked, leading me to sometimes surprising musical conclusions. In the end I think I arrived at something of a real collaboration between my music and theirs.”

While Glass cites the duo of Bowie and Eno as using techniques and procedures from the world of new and experimental music, Bowie and Eno themselves had been directly influenced by Glass’ work of the early 1970s. Glass maintains that his choosing to use this music which is widely seen as being part of rock or popular music, was akin to the old tradition of composers using source music in symphonies, rhapsodies, or themes & variation type compositions. One needs only think of composers like Brahms, Bartok, Copland or Dvorak using folk tunes in their work. The novelty of Low Symphony was that here we had a serious art composer using the popular music of his time. Then there’s also the obvious play on a “Low Symphony” coming from a downtown composer, invading “High” culture with the melodies of Bowie and Eno through the vehicle of a classical symphony. The original Bowie album “Low” dates from 1977 and is part of what is now known as the Berlin Trilogy (Low, Heroes, Lodger). Trying to kick a cocaine habit Bowie moved from Los Angeles to Berlin and began a now legendary collaboration with artist Brian Eno. Some of the music on Bowie’s “Low” was originally destined for Nicolas Roeg’s film The Man Who Fell to Earth. In approaching the composition of a full scale symphony, for Glass is was a simple as “These two musicians wrote beautiful melodies.”

1992 was an interesting point in Glass’ career to compose this piece. After obtaining his Master’s from Juilliard in composition in the late-1950’s, in the early 1960’sGlass went to work as a composer-in-residence in the Pittsburgh public school system. The ever prolific composer wrote all sorts of works at this time for orchestra including a violin concerto, divertimenti, and other works in the classical tradition. These pieces have all been discarded or disavowed. It was only after Glass’ time in Paris in the mid-1960s that he developed his first vocabulary as a mature composer; this would be the music that most people associate with his own unique compositional voice starting in Paris in 1965 with the incidental music to Samuel Beckett’s Play.

Shortly after Paris and travels in India, Glass returned to New York City and made his debut with his new music at the Cinematheque in May 1968. But this was early solo music or music for his own group The Philip Glass Ensemble. It would be only years later with the commission for his second opera Satyagraha that the composer would write for orchestra again. So for almost 20 years between the his “Pittsburgh” pieces in the very early 1960’s until the Satyagraha premiere in 1980 that Glass did not write for orchestra. Keep in mind that in 1980 Glass was well into his mature music and in a rich period of discovery within his own post-Einstein on the Beach style. One can see in pieces like Koyaanisqatsi (1981) and the opera Akhnaten (1983) that Glass had very clearly begun move away from the sounds and instrumentation of his own ensemble (woodwinds, keyboards, voice) to enjoy the wider palette of the what the orchestra offered and to bend his musical voice to work well within the medium.

It was by no means a given that Glass’ musical language would work so well for orchestra. Writing for the opera house greatly prepared the composer for writing concert music though with one big difference. When writing symphonies the language of music is the subject of the work. When writing operas the subject of the opera is the subject. In writing operas a composer is given weeks of rehearsals to work on the music and usually a generous amount of orchestral rehearsals. By contrast, in modern times a composer is lucky to get a complete read through of his new concert work before its premiere. With the experience of writing so many operas before attempting to compose his own first symphony Glass had the benefit of lots of experience with the orchestra as well as writing in long-form.

The trajectory of Glass’ post 1965 career is such that the composer describes himself as a “theater composer.” With his early work in Paris in the 1960’s, his work in the 1970s with Mabou Mines and experimental theater, one could easily share Davies’ concern that Glass would be viewed only as an opera or theater composer. If Glass had lived only till the age of Beethoven (56) then we would most likely see the situation that way. However, since his first orchestral work for the concert hall at age 50, and his first symphony at 55, Glass has gone on to compose ten full scale symphonies and over a dozen concerti – arguably more (or just as much) time has been spent since the year 2000 on writing symphonies, concerti, and chamber music than on theater music. But that too would miss the fact that from Glass’ earliest student days up to and including his Minimalist period, most of what Glass wrote was “absolute music” or purely instrumental music. Glass’ early reputation was founded on being an outsider, a downtowner, and a counter culture figure (counter classical musical establishment). So to eventually come back to the form of the symphony was something of a surprise to many people including many who were very close to Glass from the early 1970s. Glass himself has stated, “There are two ways of going about it. You can start at the middle and go towards the edge. Or you can start at the fringe and come back to the center.”

So what begins to emerge is a composer who started with a classical musical formation who over time gained new interests and opportunities in the theater, whose questions about the language of music found a home and a certain usefulness of the form of the symphony as a receptacle for some of his most intense musical discourse; Glass is a composer who started with absolute music, moved into theater, and has returned (to a certain extent) to “absolute” music.

Certain tendencies of a theater composer do inform many of his concert works. With his Symphonies Nos.1,2,6,7,8, and 9 we see a trend of writing in three movements, not far in form from the feeling of the three acts of a theater work. Symphonies Nos.1,4,5,6, and 7 all have extra-musical materials, texts, or other allusions. Symphonies Nos. 1,2,3,4,8,9, and 10 are purely instrumental works.

This recording by the Sinfonieorchester Basel and its music director since 2009 is an astounding accomplishment. In the 1993 studio recording the musicians were recorded sectionally and performed to a click-track. This recording was made live at the Stadtcasino Musiksaal in Basel with the Sinfonieorchester Basel. To put it simply, Davies and the orchestra bring the music to life as it has never been heard before.

But it all started in 1992 with the Brooklyn Philharmonic ‘s commission of Low Symphony. At age 55 Glass could have no idea he’d have the opportunities to create such an elaborate body of work in the medium. Now 20 years later, starting a new relationship with a new orchestra, the Sinfonieorchester Basel, Davies decided to go back to he beginning of his symphonic collaboration with Glass and make his first recording with what we now understand and recognize as Glass’ Symphony No.1.

-Richard Guérin, 2013

Credits

Andreas Werner – Recording Engineer

Jacob Haendel – Recording Engineer

Franziskus Theurillat – Director

Yannick Studer – Production

A & R and Special Projects Director: Richard Guérin

Digipack cover photo: David Parsons

Booklet cover photo: Benno Hunzinger

Design: Don Christensen

Philip Glass’s music is published by Dunvagen Music Publishers, Inc.

Executive Producers for Orange Mountain Music: Philip Glass, Kurt Munkacsi and Don Christensen

Buy

Related

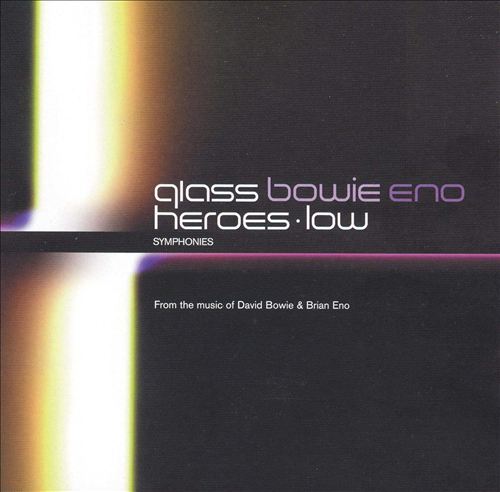

From the Music of David Bowie & Brian Eno

The American Composers Orchestra — Dennis Russell Davies, principal conductor

The Brooklyn Philharmonic Orchestra — Dennis Russell Davies, principal conductor

Catalog

Tracks

1 Heroes 5:53

2 Abdulmajid 8:53

3 Sense of Doubt 7:20

4 Sons of the Silent Age 8:18

5 Neuköln 6:41

6 V2 Schneider 6:48

CD TWO: LOW

1 I “Subterraneans” 15:07

2 II “Some Are” 11:17

3 III “Warszawa” 15:57

Remarks

Buy

Related

Symphony No. 4 “Heroes”

Symphony No. 1 “Low”

RECORDINGS:

“Low” Symphony on Point Music

“Heroes” Symphony on Point Music