Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra

Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra

Dennis Russell Davies, conductor

Catalog

Tracks

1. Movement I 4:38

2. Movement II 6:15

3. Movement III 10:06

4. Movement IV 3:29

INTERLUDE No. I from THE CIVIL WARS

5. Interlude No. 1 from the CIVIL warS 5:34

MECHANICAL BALLET from THE VOYAGE

6. Mechanical Ballet from The Voyage 5:51

INTERLUDE No. 2 from THE CIVIL WARS

7. Interlude No. 2 from the CIVIL warS 3:51

THE LIGHT

8. The Light 21:23

Notes

Composed for the 19 string players of the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra, Philip Glass’s Symphony No. 3 was designed to treat every musician as a soloist. “The work fell naturally into a four-movement form,” Mr. Glass has written, “and even given the nature of the ensemble and solo writing, [it] seems to have the structure of a true symphony.” He continues:

The opening movement, a quiet, moderately paced piece, functions as prelude to movements two and three, which are the main body of the Symphony. The second movement mode of fast-moving compound meters explores the textures from unison to multiharmonic writing for the whole ensemble. It ends when it moves without transition to a new closing theme, mixing a melody and pizzicato writing. The third movement is in the form of a chaconne, a repeated harmony sequence. It begins with three celli and four violas, and with each repetition new voices are added until, in the final [variation], all 19 players have been woven into the music. The fourth movement, a short finale, returns to the closing theme of the second movement, which quickly re-integrates the compound meters from earlier in that movement. A new closing theme is introduced to bring the Symphony to its conclusion.

A string orchestra has its own sound that is both rhythmic and lyrical, a mixture of the bite of horsehair on strings, the plonk of pizzicato, and a singer’s long cantabile phrases. In the Symphony’s first movement, Philip Glass uses this attribute to show just how suspenseful C major can be. It has the character of a gripping movie score, thanks to its ventures into the dark, “flat” side of its harmony. In the second movement, slashing unison figures seem to recall the classic American symphony for strings, William Schuman’s Symphony No. 5 of 1943. Mr. Glass also returns to his own earlier ideas in the third movement, with its deep string tone, syncopated rhythm, repeating chord progression, and vocal violin solo reminiscent of works such as the opera Akhnaten. The vigorous finale chugs to a 3+3+2 rhythm, punctuated by strange chromatic passages that yank the music into new harmonic territory.

the CIVIL warS (1984) was commissioned by Teatro dell’Opera di Roma; première March 1984, at Teatro dell’Opera, Rome, Italy.

Glass composed the music for Act V, the final act of Robert Wilson’s colossal stage piece the CIVIL warS: a tree is best measured when it is down, a day-long work intended for the Olympic Festival of the Arts at Los Angeles in 1984. Abraham Lincoln, Mary Todd Lincoln, Robert E. Lee, and personages from Native American and Greek mythology were among the figures who traversed the stage, singing in several languages and creating multiple visual tableaux.

“Wilson needed time for a scene change in a couple of places, and asked me for some music,” Mr. Glass recalls. “I composed a sort of pause, a respite from the stage action. They were quiet pieces.” One hears the distant sounds of Wagnerian horns or the exotic suggestions of the “Arabian Dance” from Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker. The influence of the latter work, and especially the descending-scale theme of its grand pas de deux, stands out in the second interlude.

The Voyage (1992) was commissioned by Metropolitan Opera in commemoration of the 500th anniversary of the discovery of America; première October 12, 1992, at the Metropolitan Opera House, New York.

Between the two CIVIL warS interludes, we hear the “Mechanical Ballet” from Mr. Glass’s opera The Voyage, composed in 1992 to commemorate Columbus’s journey to America. The stage action brings together events widely separated in time, including not just Columbus’s voyage, but a future space mission and a visit to earth by an alien spacecraft in prehistoric times as well. Alter the latter’s arrival, an instrumental interlude was called for, which (according to Mr. Glass) the opera’s director David Pountney dubbed the “Mechanical Ballet”. As far as Mr. Glass knows, no reference to Ballet mécanique, the notorious 1925 piece by the American modernist George Antheil, was intended. For his part, the composer cites Verdi’s Requiem and his own Einstein on the Beach as the main influences on this music.

The Light (1987) was commissioned by Michelson-Morley Centennial celebration; première October 29, 1987, by the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra, Cleveland, Ohio.

“In school, I thought I’d want to be a scientist,” Mr. Glass recalls. This is reflected in a number of his compositions: he has written about Einstein, based a character in The Voyage on the cosmologist Stephen Hawking, and is even involved in a prospective opera about Galileo. “The suggestion,” he has written, “to write music to commemorate the anniversary of the Michelson-Morley experiment at Case Western Reserve University in 1887 was one to which I could respond immediately.”

In their simple yet revealing landmark experiment, the American physicists Albert A. Michelson and Edward W. Morley used mirrors to split, reflect, and recombine a single beam of light, producing a fringe-like “interference pattern.” The fact that this pattern was always the same, regardless of the motion of the apparatus, demonstrated that the speed of light is always the same, regardless of the motion of the observer. This stunning result was not explained until the publication, two decades later, of Einstein’s theory of relativity.

In The Light, Mr. Glass depicts the light itself, and the inspired minds of the two scientists, by means of his most scintillating orchestration, strong on piccolo, trumpet, and violin arpeggios. Discovered by Americans, these light waves and particles seem to be dancing a foxtrot. Mr. Glass comments:

In a way, these experiments formed in my mind an almost ‘before and after’ sequence. The ‘before’ represented something like 19th century physics. The ‘after’ marks the onset of modern scientific research. Perhaps this may appear somewhat simplified from a scientific point of view, but for a musician it provided a dramatic contrast.

The music begins with a slow, romantic introduction and leads abruptly to the main body of the work — a rapid, energetic movement, which forms the balance of the music. The opening bars are heard again just before the final moments and the music ends quietly.

I have described this one-movement work as a portrait. In the past I have written portrait operas — Einstein, Gandhi, Akhnaten are the subjects of the first trilogy. In this case, this is a portrait not only of the two men for whom the experiments are named but also that historical moment heralding the beginning of the modern scientific period.

— David Wright

Credits

Symphony No. 3 (1995) and Interludes from the CIVIL warS (1984): Performed by the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra. Conducted by Dennis Russell Davies. Recorded October 1996 at the Liedrkranzhalle, Stuttgart-Botnang. Engineer: Roland Rublé, Südwest-Tonstudio. Assistant Engineer: Wolfgang Mittermaier.

Mechanical Ballet from The Voyage (1992) and The Light (>1987): Performed by the Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra. Conducted by Dennis Russell Davies. Recorded September 1996 at the Austrian Broadcasting (ORF) Studios, Vienna. Engineer: Anton Reininger. Assistant Engineers: Robert Pavlecka, Stefan Lainer. Mixed at The Looking Glass Studios, New York. Engineer: Martin Czembor. Assistant Engineer: Ryoji Hata.

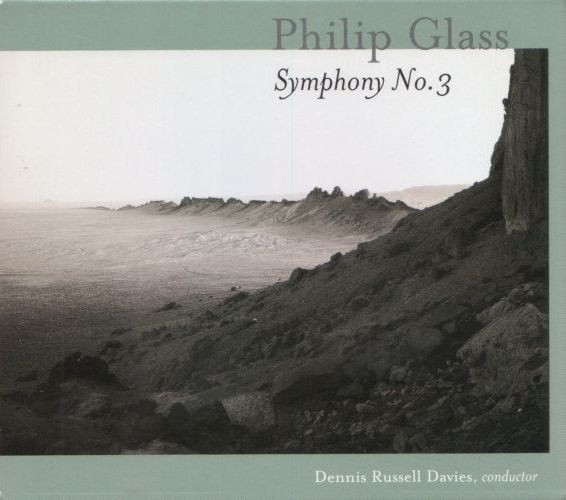

Design by Frank Olinsky. Cover photograph: Desert Form #1 (New Mexico) by William Clift. Inlay photograph: Desert Form #4 (New Mexico) by William Clift. Photo of Philip Glass by Brigitte Lacombe.

Thanks to Veronica Arroyo, Jim Keller, Ramona Kirschenman, Amanda Riesman, Herbert Schröder, Andrea Seebohm.

Music Published by Dunvagen Music Publishers, Inc. (ASCAP). © 2000 Nonesuch Records for the United States and WEA International Inc. for the world outside of the United States.

Buy

Related

Philip Glass — The Symphonies

The Hours

Glass: Symphony No.3 – The Hours

Music from The Hours (Solo Piano) on Orange Mountain Music

Philip Glass Film Scores on Orange Mountain Music

Glass Piano Music on Orange Mountain Music

COMPOSITIONS:

Symphony No. 3

The Hours

the CIVIL warS – Rome

The Voyage

The Light

Performed by Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra

Marin Alsop, Conductor

Catalog

Tracks

1. I. 4:27

2. II. 6:17

3. III. 9:38

4. IV. 3:32

SYMPHONY NO. 2

5. I. 16:42

6. II. 13:23

7. III. 13:08

Notes

Born in Baltimore in January, 1937, Glass became familiar with music through his father, who was a radio repairman and record salesman. After attending the University of Chicago, where he studied mathematics, with music as his principal distraction, he went to New York to study at the Juilliard School. There he was extremely prolific, though he was writing music that is nothing like the work we know him for today. Like all good composers of his generation, he went to Paris to study with Nadia Boulanger, the twentieth century’s greatest teacher, but it was not through her tutelage that the apocryphal scales would fall from his eyes, but through a fortuitous work-for-hire job he got transcribing and notating Indian music played by Ravi Shankar. He withdrew all his earlier work, and began to use these Eastern techniques in his experimental music.

Glass formed his own, self-named ensemble – his approach was, and has always been, very D.I.Y. – and wrote long, repetitive process pieces for them, the most famous of them being Music in Twelve Parts (an evening length concert work) and Einstein on the Beach (a full-scale opera, and his first collaboration with director and co-visionary Robert Wilson). These stillinfluential works serve as a pair of musical “shots heard ‘round the world” for many members of New York’s downtown experimental set. As he eschewed the usual concert music venues, playing, instead, in the lofts, art galleries and clubs which populated pre-commercial SoHo and TriBeCa in the mid-1970s, his reputation, both as saint and blasphemer (depending on who you asked) grew.

The Philip Glass Ensemble continues to tour regularly with many of the same members, and though he has written much music for them, a large portion of his output continues to be for more traditional groups: there are string quartets, concertos, tone poems, film scores, operas, and symphonies. And lately his bad reviews have turned good (proving the notion that to get good notices in the New York press, one only need persevere long enough). He continues, at this date, to be as prolific as ever.

The Second Symphony was originally commissioned by the Brooklyn Academy of Music, and its première took place in 1994 there, with Dennis Russell Davies (a staunch Glass advocate, commissioning most of his orchestral music) conducting the Brooklyn Philharmonic orchestra. It is cast in three movements, large paragraphs (as Glass is wont to do), more invested in polytonality, where music is in more than one key simultaneously, than many of his other more straightforward pieces, with the exception of his big opera Akhnahten. “The great experiments in polytonality carried out in the 1930s and 1940s show that there’s still a lot of work to be done in that area,” says Glass, but, unlike the major experimenters with this sort of sound world (most notably French composers like Honegger and Milhaud) who just sort of shoved one key atop another to make for rather crunchy harmonies, dissonances that bend the ear yet still have all the benefits of normal tonal motion, form, and cadence, Glass is more interested in the ambiguity this sort of language creates. It is the aural equivalent of looking at an Escher print – you hear things differently depending on where you choose to focus your ear.

The first movement is something of a slow burn, building in intensity, dank and a little screechier than many of Glass’s “prettier” works, but ending in a calculated whimper; the second movement picks up where the first left off, equally dark, with a persistence and a sombre quality which one might hear as somewhat despondent; the final movement, contra all the fascinating murk of the preceding two, is spirited and bright, favoured by bells and whooshing woodwinds, all swirling to a barnburning conclusion.

Though it bears the same title, Glass’s Third Symphony is quite a different experience from the second. This piece, composed on a smaller scale, was commissioned by the Würth Foundation for the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra, who gave the first performance in Künzelsau, Germany, in February, 1995. When writing for a chamber orchestra, nineteen string players in this instance, it becomes less about orchestral texture and timbre, more about soloistic playing, with each instrumentalist functioning more like a member of a string trio or quartet than of an orchestra. With this in mind, Glass composed a much denser, more intimate piece, cast this time in the traditional symphonic four movements.

“The opening movement,” writes Glass (in liner notes to a prior recording), “a quiet, moderately paced piece, functions as a prelude to movements two and three, which are the main body of the symphony. The second movement mode of fast-moving compound meters explores the textures from unison to multiharmonic writing for the whole ensemble. It ends when it moves without transition to a new closing theme, mixing a melody and pizzicato [plucked strings as opposed to being bowed] writing. The third movement is in the form of a chaconne, a repeated harmony sequence. It begins with all three celli and four violas, and with each repetition new voices are added until, in the final variation, all nineteen players have been woven into the music. The fourth movement, a short finale, returns to the closing theme of the second movement, which quickly re-integrates the compound meters from earlier in that movement. A new closing theme is introduced to bring the Symphony to its conclusion.”

In both of these pieces, Glass returns (in his way) to his Juilliard roots, writing polyharmonies, rousing finales, and fully formed symphonic sprawls which are far more redolent of, say, the Vincent Persichettis or the William Schumans of his graduate school training than the Laurie Andersons or Terry Rileys of the SoHo 70s. These symphonies, though longish in duration, are taut, constructed works, bearing their name not out of flash but rather out of design. He did not just compose big pieces for orchestra and attach a classy title, for these pieces truly are symphonies in their scope, intention, and seriousness of purpose.

– Daniel Felsenfeld