The Philip Glass Ensemble

Catalog

Tracks

2 Contrary Motion 15:31

3 Music In Fifths 23:19

4 Music In Similar Motion 17:11

Notes

The acknowledged, university-supported, musical avant-garde of the late 1960s was a combination of European-derived serialism (exemplified by Milton Babbitt and his acolytes) and the scrappy, anarchic, aleatory work of John Cage. Both of these musics, despite their very different origins and intentions, shared the same prohibitions and every composition student knew what they were. Consistency of any sort was to be shunned: budding composers were instructed to avoid suggesting a tonal center, to stay away from direct repetition, and to accept the fact that Stravinsky had had the last word on steady rhythmic pulsation. And along came Philip Glass, blasting out his stark, obsessive reiterative patterns at maximum volume, to stand all of the rules on their head.

He was, in many ways, an unlikely radical. Born in 1937, Glass grew up in Baltimore, where his father owned a record store. He began his formal musical studies at six, playing violin, but soon turned his attention to the flute. At fourteen, Glass passed an early-entrance examination into the University of Chicago, where he matriculated in the fall of 1952, and took his bachelor’s degree in 1956. He then moved to New York to study composition at the Juilliard School with William Bergsma and Vincent Persichetti, and later with Darius Milhaud and Charles Jones at the Aspen Music School.

By this point, Glass had begun to establish his germinal style which, he later acknowledged, owed a great deal to the influence of Milhaud. Several early pieces were published but the composer has disavowed everything he wrote before 1965.

Glass found himself increasingly dissatisfied with the music he was writing and, indeed, with the musical milieu of the time. “Though there were many gifted and energetic composers and performers dedicated to serialism, the music to this day has not found general acceptance,” he wrote in 1987. “It was music I had studied as a student and any further exercise of that kind interested me not at all. To me, it was music of the past, passing itself off as music of the present. After all, Arnold Schoenberg was about the same age as my grandfather.”

Glass went to Europe in 1964, where he eventually settled in Paris to study harmony and counterpoint with the legendary pedagogue Nadia Boulanger. During his second year with Boulanger, he was engaged to transcribe a film score by sitar player Ravi Shankar into Western notation for Parisian studio musicians.

“What came to me as a revelation was the use of rhythm in developing an overall structure in music,” Glass later wrote. “I would explain the difference between the use of Western and Indian music in the following way: In Western music we divide time — as if you were to take a length of time and slice it the way you slice a loaf of bread. In Indian music (and all the non-Western music with which I’m familiar), you take small units, or ‘beats,’ and string them together to make up larger time values.”

Following this new fascination, Glass spent the last part of 1966 and the first months of 1967 in India. Upon his return to the United States, he worked again with Shankar, who was then a visiting professor at the City College of New York, and with the tabla player Alla Rakha. He also grew close to several other young composers, particularly Terry Riley, Steve Reich and Jon Gibson, who were pursuing similar interests in lower Manhattan; the association with Gibson continues to this day.

In 1968, Glass presented the first concert of his music at the Film-Makers Cinematheque in New York. The program included Strung Out, for solo violin, and Music in the Form of a Square, for two flutes. The same year, he put together the first Philip Glass Ensemble, an aggregate of amplified keyboards, voices, saxophones and flutes (also, on occasion, trumpet and violin) that would remain his principal means of musical expression for more than a decade and a key element of his creative life well into the 1990s.

Glass’s early music was aggressively reductive in its form, melodic content and harmonic language. The names of the works on this album — Two Pages, Contrary Motion, Music in Fifths and Music in Similar Motion— are not only titles but apt summations of what actually happens in the compositions that they describe.

Two Pages is the earliest, and the most spartan, of the four; Glass believes it was written in 1967 or 1968. In this study in the elongation and subsequent contraction of a simple musical line, Glass explored what he called his technique of “additive process,” derived from his work with Shankar, in its most skeletal manifestation.

Contrary Motion, composed in 1969 for solo organ, is not quite so austere; pedal points add a functional harmony (A minor) and there is something faintly Bach-ian about its stern, rigorous counterpoint. Contrary Motion was written in what Glass calls “open form” — it never really ends, it just stops. The expanding figures upon which it is constructed could, theoretically, continue augmenting forever. Should an interpreter care to take it that far, a performance lasting hours, even days, would be possible.

Music in Fifths (1969), on the other hand, is in “closed form” — a predetermined structure that ends when the accumulation of repetitions fill it out completely. Glass has always considered Music in Fifths a sort of teasing homage to Boulanger; it is written entirely in parallel fifths, a cardinal sin in the traditional counterpoint his teacher so carefully instructed.

The most appealing of these works — and the only one that the Philip Glass Ensemble still keeps in its active repertory — is Music In Similar Motion (1969). “The real innovation in Similar Motion is its sense of drama,” Glass said in 1993. “The earlier pieces were meditative, steady-state pieces that established a mood and stayed there. But Similar Motion starts with one voice, then adds another playing a fourth above the original line, and then another playing a fourth below the original line, and finally a bass line kicks in to complete the sound. As each new voice enters, there is a dramatic change in the music.”

In the years after these works were composed, the Philip Glass Ensemble presented concerts in the lofts and galleries of Manhattan’s nascent Soho district, where such artists as Richard Serra were creating their own visual “process pieces.” “People would climb six flights of stairs for a concert,” Glass recalled. “We’d be lucky if we attracted an audience of twenty-five, luckier still if half of them stayed for the entire concert.” Then, as later, audience response was mixed. Some listeners were transfixed by the whirl of hypnotic musical patterns created by the ensemble, while others were bored silly, hearing only what they considered mindless repetition.

Still, Glass realized he was building a following and, with the business acumen he has demonstrated throughout his career, he privately produced his first recordings, which disseminated his work to home audiences and venturesome radio stations. Now, nearly a quarter century on, with the reissue of these rowdy, precious souvenirs, latter-day listeners can track the course of a tremendously important and influential aesthetic. This is where it began.

— Tim Page

Credits

Two Pages: Philip Glass, electric organ. Michael Riesman, piano.

Contrary Motion: Philip Glass, electric organ.

Music In Fifhts: Philip Glass, electric organ. Jon Gibson, Dickie Landry, soprano saxophones. Kurt Munkacsi, engineer, electronics.

Music In Similar Motion: Philip Glass, Steve Chambers, Art Murphy, electric organs. Jon Gibson, Dickie Landry, soprano saxophones. Robert Prado, flute. Kurt Munkacsi, engineer, electronics.

Contrary Motion and Two Pages: From the Shandar recording Solo Music. Produced by Kurt Munkacsi-Philip Glass-Shandar. Recorded March 1975 at Basement Recording Studio, NYC. Engineer: Kurt Munkacsi.

Music In Similar Motion and Music In Fifths: From the Chatham Square Productions recording Music In Similar Motion and Music In Fifths. Produced by Philip Glass and Klaus Kertess. Dedicated to Robert Prado (1938-1972). Music In Similar Motion: Recorded June 1971 at Martinson Hall of The Public Theatre, NYC. Recording engineers: Robert Fries and Kurt Munkacsi. Remix engineer: Kurt Munkacsi. Music In Fifths: Recorded June 1973 at Butterfly Productions, NYC. Recording and remix engineer: Kurt Munkacsi.

Produced by Kurt Munkacsi and Michael Riesman for Euphorbia Productions, Ltd. Digitally remastered at The Looking Glass Studios, NYC, using SoundTools ProMaster 20 and DINR by digidesign.

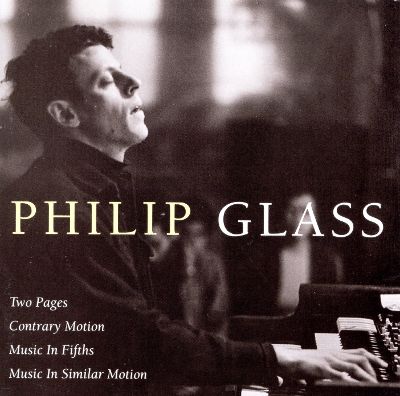

Design by James Victore Design Works. Cover Photograph © 1973 Peter Moore.

© Dunvagen Music Publishers, Inc. (ASCAP). © 1994 Orange Mountain Music