Info

Text by Robert Wilson and Maita di Niscemi

American Composers Orchestra

Dennis Russell Davies, Conductor

Catalog

Tracks

2. Scene A 15:23

3. Scene B 21:15

4. Scene C 22:10

Notes

Characteristically, Mr. Wilson found the initial inspiration for the CIVIL warS in visual images — Mathew Brady’s photographs of America’s Civil War. But as his vision of the work expanded to Olympian proportions, the art and music of many nations began to figure in it, and so did all of their “warS.” (The novel orthography of the work’s title, therefore, reflects not only Mr. Wilson’s visual sense, but also a certain emphasis in meaning that, like all his imagery, sets the viewer thinking by its complexity.) Mr. Wilson and his collaborators in several cities worked through the early 1980s on their epic, bringing the sections to various stages of completion, but in the end the Olympic Games took place without the CIVIL warS.

“Funding problems” are the conventional explanation for the work’s failure to come off as planned in Los Angeles, but one might as well say that the gigantic project collapsed from sheer world-embracing idealism. Since then, people have been curiously inspecting the fragments, either in their cities of origin (Cologne, Rotterdam, Minneapolis) or in subsequent performances elsewhere. A 1985 production in Cambridge, Massachusetts, of the work’s Cologne sections prompted an unanimous vote by the Pulitzer Prize jury to award the drama prize to the CIVIL warS in 1986; the Pulitzer board overruled the jury, however, and no drama prize was given that year.

Meanwhile, other sections of the epic work were establishing themselves in the music theater repertory. Mr. Wilson and composer David Byrne had created thirteen entr’actes, which they called “knee plays,” to connect all of the work’s scenes, and these now took on a life of their own through a recording and an extensive American tour. But it was the final act of the CIVIL warS — Act V, the “Rome Section,” commissioned by the Rome Opera and completed in 1983— that aroused the most interest in opera houses, because, like the Cologne section, it was the product of a collaboration between the creators of Einstein on the Beach, a radically new kind of opera that earned acclaim at its premiere in 1976 and has been frequently produced since.

“I became an opera composer by accident, Philip Glass told an interviewer, John Koopman, in 1990. “When Bob [Wilson] and I did Einstein on the Beach it was only technically an opera, because the only place you could do it was an opera house — you needed an orchestra pit and you needed fly space and wing space. I really had little intention of becoming an opera composer, and yet the writing I did in the first few operas — Satyagraha, for example— did, in fact, turn out to be suitable for the voice… As a young man, in the Juilliard School, I had to sing in the chorus. We did the Missa solemnis, the Verdi Requiem, and a lot of the standards. I learned these works by singing in the bass section, and it was a good form of instruction… I look back at Satyagraha now, and think that I was remarkably lucky! I was very lucky! I didn’t deserve to have written so well for the voice as I did then. I know much more about the voice now…” The Wilson-Glass “operas” do have the kind of comprehensive, Wagnerian aesthetic aspirations referred to above. But if opera fans attended one expecting an updated version of Lohengrin, they were in for a shock. It might be wiser to call these pieces by a post-Wagnerian term such as “multimedia art works,” to liberate them from the tradition of plot and subplot, of recitative and aria.

Certainly Philip Glass’s musical roots are not in the spectacle of opera, but in the small venues and small ensembles that are suited to more abstract kinds of musical thought. Mr. Glass graduated from the University of Chicago at age 19, attended the Juilliard School, and studied composition with Vincent Persichetti, Darius Milhaud, William Bergsma, and, eventually, Nadia Boulanger in Paris. Music by a senior Boulanger pupil, Virgil Thomson, influenced Mr. Glass’s style by its consonant sound and deceptive simplicity. Thomson’s operas, such as Four Saints in Three Acts and Lord Byron, emphasized theatricality over vocal display; Mr. Glass’s Einstein on the Beach was in fact an “opera” with very little singing.

Mr. Glass acknowledges that, when he later took the assignment to write the culminating act of a large theatrical work to be produced in Rome, he came face to face with nearly 400 years of Italian opera tradition. He responded to it with his most frankly operatic music to date, wading fearlessly into the full orchestra, translating the intricate patterns of musical lines he had developed in his own chamber group into an equally colorful yet lucid orchestral language. He adapted the powerful, projected style of opera singing to his own expressive ends, and was in turn influenced by it to think in long melodic lines. The result was not ersatz Puccini, but a they-said-it-couldn’t-be-done synthesis between conservative and avant-garde musical styles of the 1980s.

The traditional style of the dictatorial opera composer who dominates the librettist and director was not for Mr. Glass. In fact, he entered the project at a late stage, after Mr. Wilson had added layer after layer of text and imagery and created virtually an entire opera without music. After seeing and timing a videotape of this, Mr. Glass set to work like a film composer, tailoring his music to the action. “What I prefer in a collaboration,” he recently told the critic Mark Swed in an interview, “is to have all the other work in front of me. That becomes the source and the inspiration of theater.” As Mr. Swed goes on to observe, the Rome Section thus paved the way toward two very different theatrical achievements for Mr. Glass: his resplendent grand opera The Voyage, and his unique film-opera La Belle et la Bête, which is performed in synchronization with the classic film by Jean Cocteau.

A working definition of “minimalism” in the arts might be “doing a lot with a little.” Beethoven might have said that this was what he was doing too, but Philip Glass does so more explicitly, and in a different context. Mr. Glass’s harmonic palette, though based on the primary colors of the familiar major and minor chords, derives its expressive effect not from the gravitational pulls of a tonic key and sonata form, but from the coloristic effects of chords “related only to each other,” as Schoenberg said of notes. Far from static, Mr. Glass’s music is constantly shifting its harmonic ground, throwing his much-repeated melodic and rhythmic motives into ever-changing light.

It is customary in a booklet accompanying a recording of an opera to describe the onstage action that takes place during the music. Many people who haven’t seen the work have heard of its striking visual images: an enormously elongated figure of Abraham Lincoln in stovepipe hat and frock coat, rising from the stage during the Prologue, turning horizontal in mid-air, and floating slowly offstage; Robert E. Lee glimpsed through the porthole of a spaceship, rotating like a weightless astronaut; Giuseppe Garibaldi, atop a box, surveying a battlefield below; Hopi dancers and Garibaldi’s soldiers dancing together on a bridge between two spaceships; a procession, in the final scene, of trees from many nations. To cite a few of them is to remind the listener of the rich brew of Mr. Wilson’s visual and cultural imagination, in which no image is too historical or too futuristic, too familiar or too exotic, to contribute something to our perception of the work’s meaning. To attempt a deconstructive catalogue of these images in a listening note would rob them of the haunting effect they have as they combine and evolve in a theater.

It is wiser, for present purposes, to focus on Mr. Glass’s score as a kind of cantata, whose dramatis personae — Mrs. Lincoln, Hercules, Garibaldi, and Snow Owl, to name a few— are representative of an art work that is not just multimedia, but multinational. The words they sing, furthermore, are often not their own, but culled by the librettists Maita di Niscemi and Robert Wilson. The source material is varied, drawn from the tragedies of the Roman playwright Seneca and a variety of war narratives, including those of the American Civil War. Because of this diversity of characters and sources, even an audio recording of this work can evoke some of the immense variety of the staged version.

The Rome Section of the CIVIL warS opens as Act V of a sweeping drama should, with turbulent and dramatic music that seems to sum up “the story so far,” punctuated by a fearsome trumpet-call motive. The Earth Mother’s vision of a quiet world at daybreak calms the orchestra; as the Snow Owl and Abraham Lincoln join, the vision becomes a prayer for peace that increases in fervor. The Prologue ends on a peak of musical agitation, suggesting that the fulfillment of peace is still some way off.

In Scene A, the syncopated rhythmic cell that ended the Prologue on such an agitated note is transformed into a robust, optimistic chorus. Paradoxically, the entrance of the great Italian military hero Giuseppe Garibaldi puts a stop to this militant music; instead, he sings the praises of “water…limpid, pure” with a freedom and fluidity that evokes not only the text but generations of resplendent Italian tenors. Furthermore, Mr. Glass’s rolling arpeggios take on Verdi-like harmonic colors. The music soon recovers its headlong momentum, driven by the gunfire-like rattle of the snare drum, but the admixture of texts suggesting Hopi images of fertility and talking of “rogues, con men, talkers, traitors” puts an ironic cast on the scene. The final cry of “Rome or death!” may apply as much to the creators of this work as to Garibaldi.

Scene B is the centerpiece of the work, not only because of its position but also because of its emotional force. The American Civil War comes to center stage again, as the character Robert E. Lee speaks the words of war narratives, especially one observer’s recollection of Lee himself riding to the surrender at Appomattox. When Mary Todd Lincoln sings the text, in some of the opera’s most melodious music, an anticipation develops as to whether it refers to Lee or her own husband, and whether that matters. At times, words of other languages — French, Italian, Spanish, Vietnamese- are stirred into the text, reminding us again that “CIVIL warS” is plural. To set the scene, Mr. Glass too uses a found object: the traditional spiritual “Jacob’s Ladder,” whose syncopated phrases gently echo the agitated motive of the earlier scenes. As Southerners (born in Maryland and Texas, respectively), Glass and Wilson vividly recall congregations singing this hymn. The hymn continues almost unheard under the alto solo and the rich melody for trombone and double basses, which are related to the hymn as a descant, another old church singing tradition. The tune’s return at the close, under the most affecting images of the Lee story, clinches the scene.

The mood of Scene B colors the work’s closing scene: the Prologue’s trumpet call returns, but with a forlorn, elegiac character, and the chorus sings a kind of Miserere nobis, a prayer for mercy, that would not sound out of place in Verdi’s Requiem. But as the memories of war and heroism fade, the music slips into emotional suspense, circling round and round in C major with just the odd dissonant note here and there, sometimes recalling the syncopated and trumpet motives. Young Mrs. Lincoln speaks a Joycean stream of seemingly banal phrases from modern life, of which the precarious “I’m not mad” — does she mean angry or insane?— is doubtless the key one. After a brief echo of Abe Lincoln’s prayer from the Prologue, an octet of ancient gods and heroes sings one of Prospero’s lines from The Tempest (“Our revels now are ended”) and fades away. Hercules and his mother, Alcmene, offer words of reassurance to each other, but eventually Hercules is left totally alone, endlessly singing his circular phrase.

— David Wright

New York City, 1999

Credits

Prologue: Denyce Graves, Sondra Radvanovsky, Zheng Zhou. Scene A: Giuseppe Sabbatini; Choir. Scene B: Robert Wilson, Denyce Graves; Choir. Scene C: Laurie Anderson, Stephen Morscheck, Sondra Radvanovsky; Choir.

This piece originally premiered in March of 1984 at the Teatro dell’Opera di Roma and was conducted by Marcello Panni. These roles were originally created by: Seta Del Grande, Ruby Hinds, Luigi Petroni, Franco Sioli, Luigi Roni, and Franco Concillo.

Produced by Michael Riesman & Kurt Munkacsi for Euphorbia Productions, Ltd., New York. Recorded 1995-1999 at The Looking Glass Studios, Electric Lady Studios, and Sorcerer Sound, New York. Mixed at Electric Lady Studios, New York. Recording engineer: Rich Costey. Additional recording engineering: John Billingsley, Tim Conklin, Martin Stumpf. Mix Engineer: Tucker Burnes. Technical engineer: Jamie Mereness. Assistant engineers: Ryoji Hata, Steef van de Gevel, Tony DiCarlo. Animal montage created by Don Christensen after the original sound design of Hans Peter Kuhn. Production Coordinators: Veronica Arroyo, Amanda Riesman. Production Assitants: Dylan Drazen, Emily Shannon, Sean McCaul, Kevin Reily, Hideyuki Waki. Nonesuch Production: Karina Beznicki. Executive Producer: Robert Hurwitz.

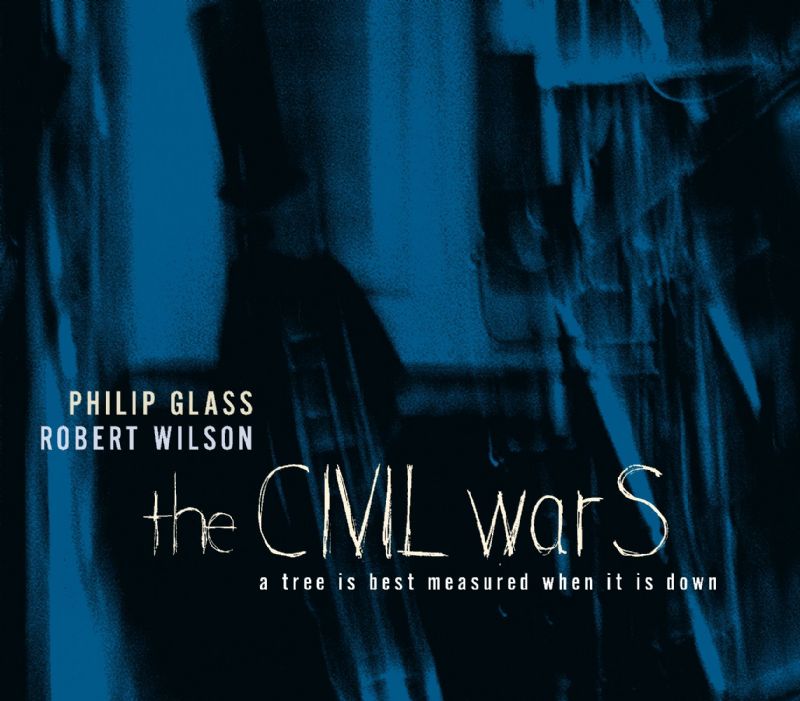

Design by 27.12 design, Ltd. Photographs © 1984, 1999 Peter Angelo Simon. Slipcase front, CD label, inside inlay: Lincoln costume (Rome production, 1984) Sketches by Robert Wilson photographed by Geoffrey Clements, courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Liner notes © 1999 David Wright.

Music published by Dunvagen Music Publishers, Inc., New York. © 1999 Nonesuch Records.

Buy

Related

the CIVIL warS – Rome