Info

Libretto by Philip Glass & Constance DeJong

The New York City Opera, Orchestra & Chorus

Christopher Keene, director

Catalog

Tracks

1. Scene 1 18:47

2. Scene 2 11:00

3. Scene 3 11:40

DISC TWO: Act II – Tagore

1. Scene 1 14:44

2. Scene 2 11:32

3. Scene 3 15:16

DISC THREE: Act III – King

1. Part 1 15:35

2. Part 2 16:13

3. Part 3 8:22

Notes

NOTES ABOUT SATYAGRAHA

The Sense of Peace

By any measure, the critical and popular acclaim awarded the composer Philip Glass, in both his native America and throughout much of Europe, is extraordinary. His three operas — Einstein on the Beach (1975), Satyagraha (1980) and Akhnaten (1983) — have been produced by several leading opera houses while the composer and his ensemble are capable of selling out Carnegie Hall one night and a mid-western rock club the next. Glass’s audience seems to defy normal categories: Conservatory students diligently analyze the composer’s unusual orchestration, while their more hedonistic contemporaries blare Glass albums from dormitory stereo systems.

Although he loathes the term, Glass is often classified as a “minimalist” composer, along with such composers as Steve Reich, Terry Riley and John Adams. His music is based on the extended repetition of brief, elegant melodic fragments that weave in and out of an aural tapestry. Listening to this music is something like watching a challenging painting that initially appears static, but seems to metamorphose slowly as one concentrates. Compositional material is usually limited to a few elements, which are then subjected to transformational processes. One shouldn’t expect Westernized musical events — sforzandos, sudden diminuendos — in this music; rather, the listener is immersed in a sonic weather that surrounds, twists, turns, develops.

Glass prefers to speak of his work as “music with repetitive structures.” His busy, tonal, aggressively rhythmic compositions would seem to mark a spiritual break with the spare, atonal and largely arhythmic world of the 50s and 60s avant-gardists. One thing is certain: Philip Glass has brought a new and enthusiastic audience to contemporary music.

Philip Glass was born in Baltimore, Mariland, in 1937, and began his musical studies at the age of eight. At fifteen, he entered the University of Chicago, where he majored in philosophy but continued what had become an obsessive study of music. After graduation, he went the route of many other young composers: four years at the Juilliard School in New York, and later work in Paris with the legendary pedagogue Nadia Boulanger. At the same time, Glass was exploring less conventional musical routes, working with Ravi Shankar with Allah Rakha. He acknowledges non-Western music as an important influence on his mature style.

In 1967, Glass returned to New York City, where he quickly established himself as an important figure in the blossoming downtown arts community. “When I first returned to the United States, my compositions met with great resistance,” Glass recalled recently. “Foundation support was out of the question, and the established composers thought I was crazy. I had gone from writing in a gentle, neo-classical style that owed a lot to Milhaud into a whole new manner of music. The time was not right for my work.”

So Glass worked as a plumber, drove a cab at night, and spent his spare time assembling an incubatory version of the Philip Glass Ensemble. The group, composed of seven musicians playing woodwinds and a variety of keyboards with amplified voices, began concertizing regularly in the early 70s, playing for free or asking for a small donation. “People would climb six flights of stairs for a concert,” Glass recalls. “We’d be lucky if we attracted twenty-five people, luckier still if half of them stayed for the entire concert.” Then, as now, audience response was mixed. Some listeners were all but transfigured by the whirl of hypnotic musical patterns the ensemble unleashed, while others were bored, hearing only what they perceived as mindless repetition.

But slowly, very slowly, the concerts gained a cult following, and then, this time suddenly, Einstein on the Beach, a collaboration with the austere theatrical visionary Robert Wilson, became the talk of the international musical community.

Einstein broke all the traditional rules of opera. It was five hours long with no intermissions, although the audience was invited to wander in and out during performances Glass’s text consisted of numbers, solfège syllables and nonsense words. The Glass/Wilson creation was a poetic look at Albert Einstein — scientist, humanist, amateur violinist, and the man who split the atom The final scene depicted nuclear holocaust, with its renaissance pure vocal lines, the blast of amplified instruments, a steady eight-note pulse, and the hysterical chorus chanting numerals as quickly and frantically as possible, this scene was a perfect musical reflection of the anxious, fin-de-siècle late 1970s.

Things were getting better. The ensemble played Carnegie Hall and sold it out, there were more engagements and more critical praise. Musical America chose Glass to be the “Musician of the Month” in April 1979. Glass collaborated with Lucinda Childs and Sol Lewitt on Dance, a multi-media event performed at the Brooklyn Academy of Music later that year. He was invited to speak in establishment conservatories, such as the Manhatten School of Music. He had arrived.

Still, I don’t think anyone was prepared for the sheer beauty and spiritual propulsion of Satyagraha. As opposed to the Spartan Einstein, which was written for the Glass Ensemble, actors and solo violin, Satyagraha is scored for more conventional forces — a full string section. woodwinds in threes, organ, six solo singers and chorus of forty. However, Glass believes that the results are still distinctly his: “The orchestra in Satyagraha sounds quite a bit like the Philip Glass Ensemble. It never occurred to me to try to create a standard orchestral sound. I want to keep my sound There is very little soloistic writing. I concentrate on mixed timbres — as if the orchestra were an organ. That’s a funny idea — most composers have used an organ to imitate the orchestra, but in my scores, the orchestra has begun to imitate the organ.”

Satyagraha is about the period that Gandhi spent in South Africa (1893-1914). In fighting to repeal the so-called “Black Act” — a law that restricted the movement of non-Eurupeans from place to place and that virtually enslaved South Africa’s substantial Indian community — Gandhi developed the concept of “Satyagraha,” or truth-force. Gandhi fought the South African authorities on the issue of the Black Act, and eventually won non-violently — by organizing hunger strikes and peaceful demonstrations. The American novelist Constance DeJong adapted the story of Gandhi’s struggle and prepared a libretto from the Bhagavad-Gita. Glass kept the opera’s text in the original Sanskrit, in an attempt to avoid upsetting the rhythm of what is, of course, a sacred text. In another bow to authenticity, Glass used only what he called “international” instruments — instruments that could be found in both America and India, in one form or another. Satyagraha was completed in early 1980 and received its first performance in Rotterdam that September.

Each act of Satyagraha takes a historical figure as a sort of spiritual guardian, watching the earthly action from above. In the First Act, the symbol is Count Leo Tolstoy. He was one of Gandhi’s inspirations thorughout his life, and the two men carried on a correspondence that lasted until the Russian’s death in 1910. Glass believes that the “same combination of the political and the spiritual is found in both Gandhi’s and Tolstoy’s writings.”

In Act Two, Rabindranath Tagore, the renowned poet and scholar who was the only living moral authority acknowledged by Gandhi, serves as the guardian. “The symbol in the Third Act is Martin Luther King, Jr.,” Glass says, “who always impressed me as a sort of American Gandhi, accomplishing many of the same things here, and in the same manner, that Gandhi did in India. Tolstoy, Tagore, and King represent the past, present and future of Satyagraha.”

Satyagraha is vastly different from the usual operatic spectacle. It is a work written entirely on a moral, even religious, plane — more ritual than entertainment, more mystery than opera. While Einstein challenged all our ideas about what an opera — even an avant-garde opera — should be, Satyagraha neatly fits Glass into the mainstream. Einstein broke the rules with Modernist zeal: Satyagraha touches all the bases, adapting the rules to the composer’s own aesthetic. The opening scene is an aria that becomes a duet, then a trio, all set down in a rich, declamatory, near-Verdian manner. Other scenes may remind the listener of Wagner, or Delius, or of the Balinese gamelan, while the finale to Act II has the same combination of deeply classical romanticism to be found in Berlioz’s Les Troyens — hyperactive woodwind triplets and all.

Still, while Glass seems to be consciously coming to terms with his forerunners, there is never a descent to parody, nor a hint of borrowing. One never doubts who the composer is. The closing measures are masterful — has the unadorned Phrygian mode ever seemed such an eloquent melody in itself, repeated as it is, some thirty times over shifting musical sands? The nuclear anxiety of Einstein seems far away, replaced by a serene power — call it truth-force, or, better still, Satyagraha — and an all-encompassing sense of peace.

— Tim Page

NOTES ABOUT THE RECORDING OF SATYAGRAHA

The musical style of Philip Glass makes special demands on performers for concentration, endurance, and rhythmic precision. Since my co-producer, Kurt Munkacsi, and I had worked together on many recordings of Glass’s music, we were well acquainted with the difficulties of recording it and had evolved techniques to facilitate the process. So, when we undertook this production of Satyagraha, we knew at the start that we would not employ the conventional method of recording an opera, which consists of doing a number of takes and then splicing parts of them together to create a complete performance. Instead, taking advantage of the technology at our disposal, we chose to build up a performance in layers, through overdubbing. (We had used overdubbing occasionally on Einstein on the Beach, somewhat more on Glassworks, and throughout on The Photographer). The result of this method is a seamless master tape which is the fruit of many separate recording sessions.

Although overdubbing has been used for many years in the popular music field, it is almost never used for classical recordings. This recording of Satyagraha is the first production to employ overdubbing on a huge scale for a work which is essentially “classical” in instrumentation and execution. There were many difficulties to overcome to realize a performance which would breathe and vibrate with the spirit of a “live” one but which was nevertheless entirely calculated in advance in terms of tempos, tempo changes, ritards, and accelerandos. But we felt that it was worthwhile to solve these technical problems for the benefits in consistency and rhythmic accuracy of performance which would result.

Furthermore, recording in layers allows greater attention to individual instrumental and vocal detail during the recording process than does the conventional method. It also allows greater flexibility in balancing the various instruments and voices during mixdown.

We selected the 3M 32-track digital machine as our master recorder. Besides providing state-of-the-art sound, this machine has the added advantage of providing noise— and dropout-free entry and exit from record mode while rolling. This makes it possible to correct an error in a continuous performance by rolling the tape from just before the error, having the performers play or sing along with the tape, and engaging the record mode only during the errant passage. If the sound levels match, the “punch-in” and “punch-out,” as they are called, will be inaudible.

We proceeded as follows: after consultation with Christopher Keene and the composer about tempos, cuts, ritards, and so on, I recorded a set of guide tracks for the entire opera, consisting of a keyboard reduction track, two or sometimes three click (metronome) tracks, and a cue track (announcing important measure numbers). The multiple click tracks were needed because of the polyrhythmic nature of much of the music. Computers were used to store the click and synthesized keyboard tracks; this enabled me to preview and alter all of the tempos and tempo changes before their transfer to master tape, at which point the performance became rhythmically “locked in”. While the computers were able to handle sudden changes in tempo and some ritards, longer ritards and accelerandos were accomplished by manually riding the tempo control during the transfer to tape. The cue track was recorded at the time of this transfer.

Then we recorded the orchestra in sections; we began with the strings; and when they had finished their parts for the whole opera, we brought in the woodwinds (Satyagraha does not call for brass or percussion instruments). After the woodwinds, we recorded the chorus, and finally the soloists. The keyboard guide track was then discarded and replaced by the organ/synthesizer part called for in the score. Finally, additional synthesizers were used to selectively and subtly enrich the original orchestration, with the composer’s consent.

There was an unusual intensity in the control booth during all of these sessions, because the drawback of the overdubbing procedure is that you cannot save one take while you are doing another; a retake always erases the previous take. Thus, irrevocable editing decisions must be made on the spot. On the other hand, making these decisions on the spot means that they don’t have to be made later, which avoids the typical problems of mismatched tempos and dynamics which plague editors of conventional recordings.

— Michael Riesman

Credits

Cast ofr Characters: M. K. Gandhi: Douglas Perry, tenor. Miss Schlesen (Gandhi’s secretary): Claudia Cummings, soprano. Kasturbai (Gandhi’s wife): Rhonda Liss, alto. Mr. Kallenbach (European co-worker): Robert McFarland, baritone. Parsi Rustomji (Indian co-worker): Scott Reeve, bass. Mrs. Naidoo (Indian co-worker): Sheryl Woods, soprano. Mrs. Alexander (European friend): Rhonda Liss, alto. Lord Krishna (Mythological character from the Bhagavad-Gita): Scott Reeve, bass. Prince / Furst Arjuna (Mythological character from the Bhagavad-Gita): Robert McFarland, baritone. Non-singing parts: Count Leo Tolstoy Historical figure, Act I. Rabindranath Tagore Historical figure. Act II. Martin Luther King. Jr. Historical figure, Act III.

Chorus: Marilyn Armstrong, Lee Bellaver, George Bohachevsky, Frank Burzio, Don Carlo, Mervin Crook, Harris Davis, Neil Eddinger, Gori Eddinger, Arthur Giglio, Harriet Greene, Jonathan Guss, Don Henderson, Lila Herbert, John Lewis, Barbara Lindon: Rita Metzger, Madeline Mines, Ray Morrison, Stephen O’Mara, Roxanne Onori, Louis Perry, Randolph Peyton, Bridget Ramos, Glenn Rowen, Maryann Rydzeski, Deborah Saverance, Susan Schafer, Kay Schoenfeld, Catherine Williams, Mane Young, Edward Zimmerman.

Orchestra: Violin: Frederick Buldrini, Alicia Edelberg, Otto Frohn, Anne Fryer, Michale Gillette, Yana Goichman, Cora Gordon, Abram Kaptsan, Jack Katz, Barbara Long, Martha Marshall, Alan Martin, Nancy McAlhany, Martha Mott, Junko Ota, Yeugenia Pakman, John Pintavalle, Secondo Proto, Meyer Schumitzky, Myra Segal, Helene Shomer, Shirley Siegelman, Frederick Vogelgesang. Viola: Robert Benjamin, Donald Dalmaso, Laurance Fader, Susan Gingold, Warren Laffredo, Jesse Levine, Jack Rosenberg. Cello: Robert Gardner, Alla Goldberg, Esther Gruhn, Eleanor Howells, Charles Moss, Bruce Rogers. Double Bass: Richard Beeson, James Brennand, Naoyuki Miura, Harold Shachner. Flute: Gerard Levy, John Wion. Flute & Piccolo: Florence Nelson. Clarinet: Mitchell Estrin, Larry Guy, John Moses. Clarinet & Bass Clarinet: Aldo Simonelli. Oboe: Livio Caroli, Leonard Arner. Oboe & English Horn: Doris Goltzer. Bassoon: Cyrus Segal, Bernadette Zirkuli. Keyboards: Michael Riesman. Chorus Coach: Joseph Colaneri. Concert Master: John Pintavalle. Contracor for the Chorus: Randolph Peyton. Contractor for the Orchestra: Secondo Proto. Piano and Guide Tracks: Lorene Forsyth. Additional Conducting: Michael Riesman & Kurt Munkacsi.

Recording Engineers: Dan Dryden, Joe Lopes. Digital Engineer: Mark Good. Mixed by Dan Dryden, Michael Riesman, Kurt Munkacsi. Recorded and mixed at RCA Recording Studios, New York, N.Y. Additional recording: Digital by Dickinson, Bloomfield, New Jersey. Digital multi-track supplied by Digital by Dickinson. Mastered by Bill Kipper, Masterdisk, New York, N.Y.

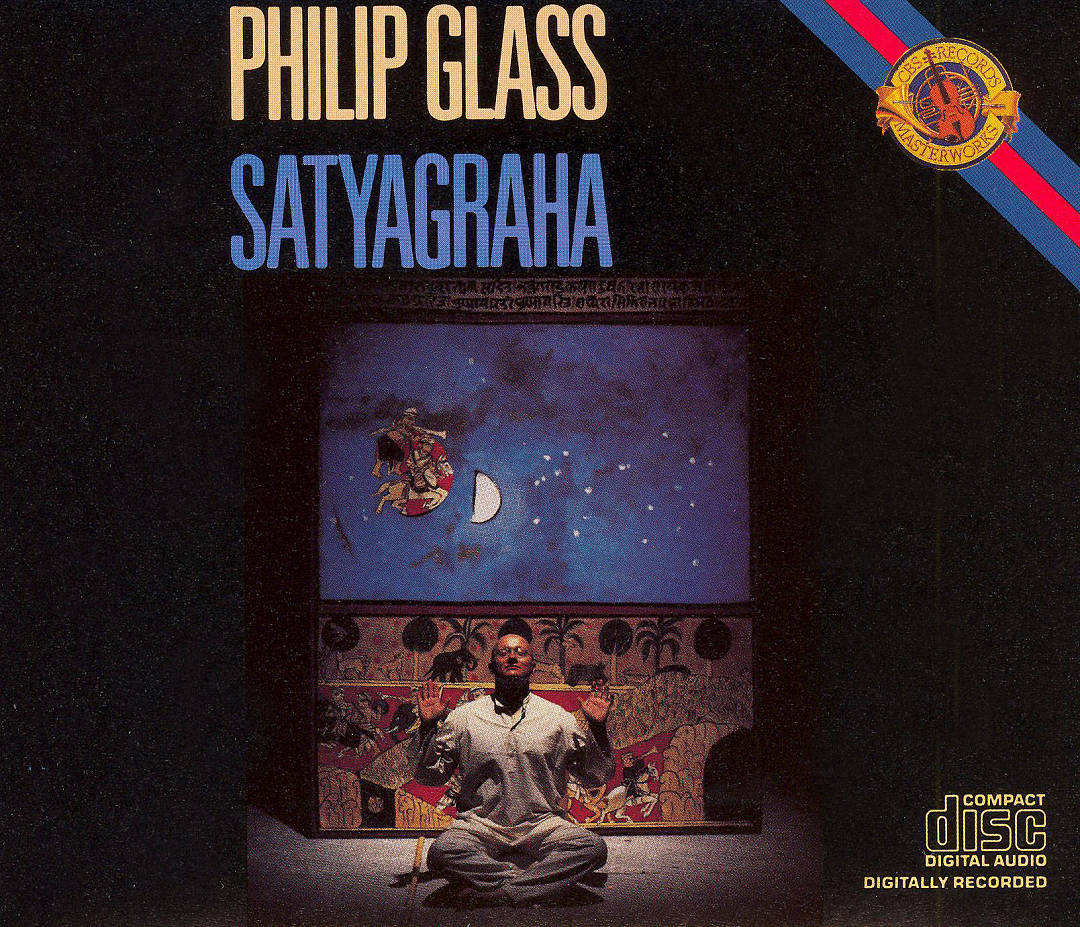

Cover photo: Harry M. DeBan. © Harry M. DeBan. Album design: Geoffrey Winston. Booklet design: Thumb Design Partnership, London.

Music published by Dunvagen Music Publishers, Inc.. New York, N.Y. © 1985 Sony Music Entertainment Inc.

Buy

Related

Satyagraha

RECORDINGS:

Glass Masters on Sony Masterworks

Songs from the Trilogy on Sony Masterworks

The Essential Philip Glass on Sony Masterworks

The Hours on Nonesuch

Music from The Hours (Solo Piano) on Orange Mountain Music

FILMS:

Satyagraha by Staatsoper Stuttgart (Dennis Russell Davies, Conductor)

BOOKS:

Music by Philip Glass by Philip Glass

Satyagraha by Constance DeJong and Philip Glass

Sakrales Musiktheater im 20. Jahrhundert: Eine Studie zur Oper “Satyagraha” von Philip Glass by Michael Altmann