Glass Chamber Players

Wendy Sutter, Artistic Director

Catalog

Tracks

2. String Sextet – Movement I 4:41

3. String Sextet – Movement II 5:52

4. String Sextet – Movement III 10:29

5. String Sextet – Movement IV 3:12

Remarks

Despite Philip Glass’ wide-ranging career of over 50 years, in recent times the composer had not been focusing on chamber music with his last string quartet, no.5, dating from back in 1991. However beginning in 2007 with his solo cello suite, Songs & Poems, composed for cellist and GCP Artistic Director Wendy Sutter, he began composing a series of chamber works including his 2008 Four Movements for Two Pianos, Sonata for Violin and Piano written for GCP member Maria Bachmann in 2009, and a large suite for solo violin written for GCP member Tim Fain in 2010.

Notes

Philip Glass was born in pre-WWII Baltimore Maryland in 1937. The composer frequently tells the story of how his father Ben Glass, who had an auto-mechanic shop in the 1930s, frequently worked on people’s cars, which led to fixing the car radios, then Ben got rid of the cars in favor of a store that sold and repaired radios. As a sideline to the radio business Ben Glass would sell some records as a small part of the business. It grew to be a big part of the business finally becoming a proper record store.

Much has been made about Philip Glass’ sense as a businessman. Growing up in this American entrepreneurial environment, the young Philip would learn his first lessons in the music business. He would see people hand a five-dollar bill to his father and his father would hand them a record. “There’s nothing wrong with that.” Glass would later say. This was his first exposure to what for many is a complicated relationship of art and commerce in America. For a composer who would eventually take part in changing the course of music history, it’s difficult to disregard the practical business sense which was ingrained in him from day one while working in his father’s record shop.

In another story, Glass would tell of the “return privilege” which was part of the record industry in which retailers were allowed to return a certain percentage of the records if they were damaged. In order to exercise this privilege, Philip and his brother Marty would go down into the basement and break the records that had not sold. This was the first job that Philip Glass ever held in the music industry.

Such an action was a logical answer to a problem: what to do with the records that didn’t sell? Being a very practical guy, as we saw with the evolution of his businesses, Ben Glass had another idea. He would take the records home and listen to them to try to find out why people weren’t buying them. It just so happens that the music which was not selling was classical and 20th century chamber music by composers like Schoenberg, Shostakovich, and Bartok. It was in this way that the Glass home record collection of 78s grew and that a very big part of Philip Glass’ artistic sensibilities were first cultivated. The soundtrack of Philip Glass’ youth had been created.

It is important to the history of music is that Philip Glass spent time as a young person at home with his father listening to chamber music records. Ben Glass was not an educated musician, but he was a music lover in best sense. In the process of listening to these records to “find out what was wrong with them,” he became a sophisticated listener and developed a taste for chamber music. Father Glass would bring Philip in to the room and simply say to the future composer, “Here kid, listen to this.” Years later, after his father’s death, Glass composed his first concert-work as a mature composer, his Violin Concerto No.1 in 1987. He composed it as a piece that he hoped his father would have liked in the tradition of the great concertos by such composers as Mendelssohn, Sibelius, and Tchaikovsky concertos.

We see that during Philip Glass’ formation as a composer, chamber music of the kind which is presented on this record, had always been a part of his musical identity. After graduating from the University of Chicago, while working at Bethlehem Steel, and during years of study at Juilliard, and with Nadia Boulanger in France, with Albert Fine in New York, with Darius Milhaud in Aspen, Glass composed chamber music constantly. This was ‘early’ music that Glass categorizes as music of a “generic modernist American sort after Copland/Harris/Schuman.” But it’s important to see that he was composing these chamber pieces from his first essays as a teenager through his mid-twenties until he found his mature voice as a composer. These juvenilia were among the up to 75 pieces while at Juilliard (over about a five year period, as Glass was not initially accepted as a composition student at the school) and another 20 or so pieces while working in the Pittsburgh School system through the Ford Foundation for two years. Examples of pieces of this time are String Quartet, Sonatino Nos. 1 and 2, Arioso Nos. 1 and 2, Serenade for Flute, “Contrasts” for violin, winds, brass and percussion.

Glass’ mature language as a composer was not fully developed until his return from France in the mid-1960s after studying with the pedagogue par excellence Nadia Boulanger (and of course Glass’ other hugely important encounter with Ravi Shankar.) As his musical language settled and matured, the Philip Glass Ensemble, a vehicle for the new music that Glass was composing, was formed essentially a chamber group. The instrumental composition of the Ensemble was partly happenstance and partly a means to a musical end; in very much the same way Schoenberg’s instrumentation was for Pierrot Lunaire. The reasons for this is because the requirements of chamber music are typically more complex the virtuosic than say your ordinary Romantic symphony. Musical language aside, the Philip Glass Ensemble, even when playing its largest pieces such as Music in 12 Parts, is still in essence a chamber group (though it must be said that Glass’ interest and subject matter for his music was for a very long time very far removed from the classical music concert hall.) With the present recording we hear Philip Glass’ mature music in a very different, yet totally appropriate context, alongside Schoenberg’s ultra-Romantic Verklarte Nacht.

There is certain elegance in Glass’ advocating to place Schoenberg on this program considering how doctrinaire Schoenberg’s disciples became about tonal composers. Clearly by the time of composing Verklaerte Nacht, Schoenberg was gearing up to challenge all of the rules of classic tonality and devise new ones. Glass has pursued his own challenges to conventional tonality that usually manifest in very individual polytonality. However, the choice of music for this release was unified not by conceptions and ideas about tonality, but by less controversial criteria: character and quality. This is return of sorts for Glass to the music of his youth (and the recordings of his youth) is significant. Glass has always described himself as a theater composer, yet on this recital, his Symphony No.3 for strings (originally for 19 string players, transcribed for sextet by Michael Riesman) stands as a piece of purely instrumental music and finds itself in perfect company with Schoenberg’s extraordinarily dark and dense Verklaerte Nacht (Transfigured Night), which was inspired by the poem by Richard Dehmel. In Dehmel’s poem, with only a few words, the reader is swooning in a sea of the complex emotions of life, and the poem’s two lovers are united by love and their own courage. Schoenberg’s musical complexity could not be more perfectly analogous to Dehmel’s words.

Not only was the repertoire carefully considered, but the way this record was recorded was as well: it was captured live in two performances at the Baryshnikov Arts Center in Manhattan in December 2009. This ‘live-recording’ sound harkens back to those classic recordings of the 1930s, 40s, and 50s before the advent of serious editing. The end result is almost always thrilling in its ebullience and pathos exactly because of the emotional arc of the performance, unencumbered by the random audible page turn or occasional ambient noise. Indeed on the nights of the recordings, there was an appropriately lugubrious rainstorm outside on the New York City streets.

This type of recording gives is a snapshot of an event that happened in real time and is an actual document of these fine players performance, and brings to full-circle a journey which Philip Glass began back in Baltimore Maryland almost 70 years ago.

Richard Guérin, New York 2010

Credits

Richard Guérin, Managing Director

Album Produced by Michael Riesman, Richard Guérin, and Don Christensen

Recorded and Engineered by Michael Riesman and Dan Bora

Edited, Mixed, and Mastererd by Michael Riesman

Recorded at the Baryshnikov Arts Center, New York, December 2009

“Sextet for Strings” arranged from Glass’ Symphony No.3 by Michael Riesman

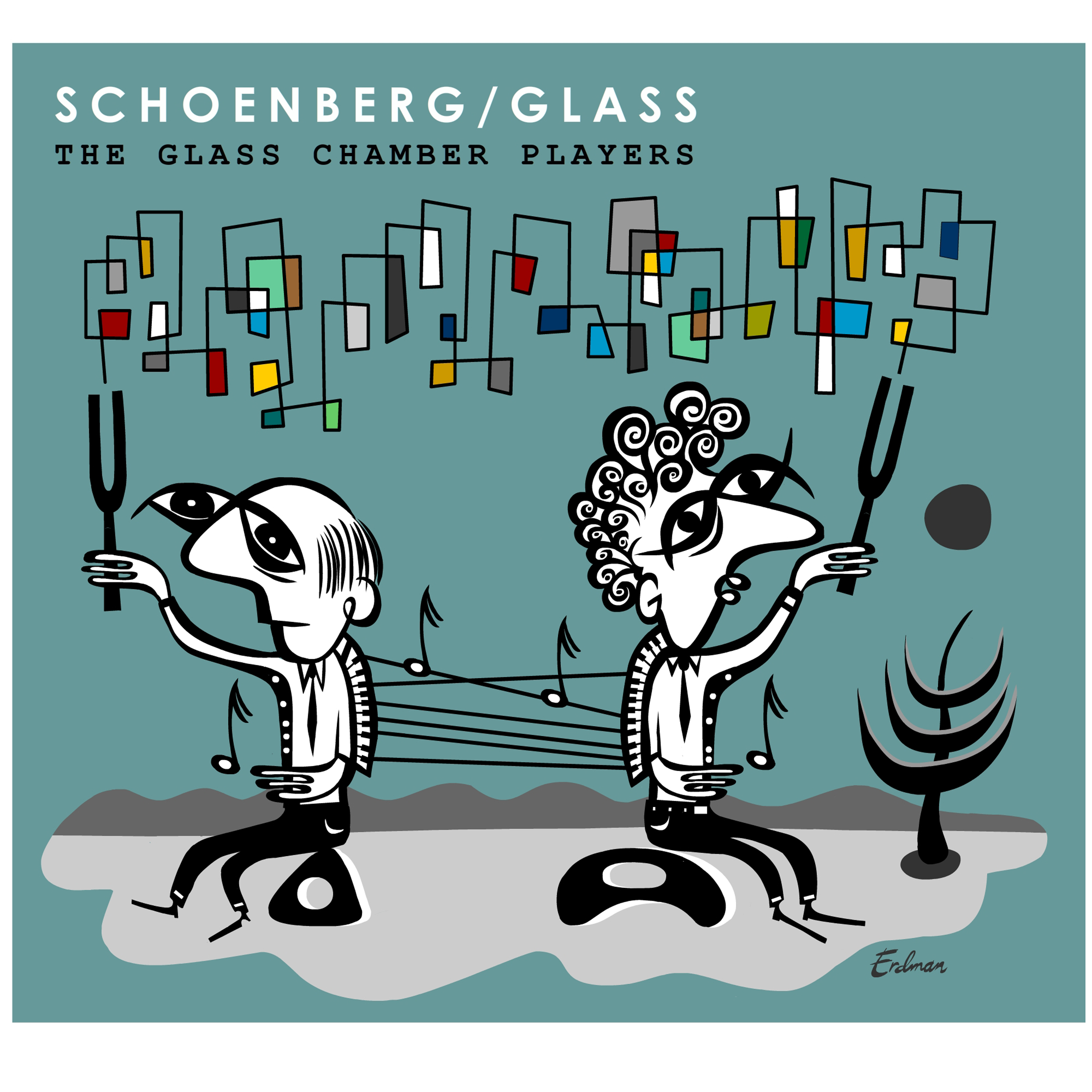

Design: Steven Erdman – www.houseoflard.com

Philip Glass’ music is published by Dunvagen Music Publishers

Executive Producers: Philip Glass, Kurt Munkacsi, and Don Christensen

Schoenberg – Verklaerte Nacht is published by Universal Editions

Glass – String Sextet (arr. of Symphony No.3) is published by Dunvagen Music Publishers, Inc. (ASCAP).

℗ and © 2010 by Orange Mountain Music.