Violin Concerto No. 1 (2017)

Summary

Music by Philip Glass / Leonard Bernstein

Bruckner Orchester Linz

Renaud Capuçon, violin

Dennis Russell Davies, conductor

Orange Mountain Music

Catalog

Orange Mountain Music (2017)

OMM 0114

Tracks

Philip Glass: Violin Concerto No.1 (1987)

1. Movement I (7:49)

2. Movement II (11:51)

3. Movement III (10:46)

Leonard Bernstein: Serenade after Plato’s Symposium for Violin and Orchestra (for Solo Violin, Strings, Harp, and Percussion)

4. I. Phaedrus – Pausanias (Lento – Allegro marcato) (7:06)

5. II. Aristophanes (Allegrotto) (4:54)

6. III. Eryximachus (Presto) (1:35)

7. IV. Agathon (Agadio) (7:54)

8. V. Socrates – Alcibiades (Molto tenuto – Allegro molto vivace) (11:41)

Notes

Leonard Bernstein excelled at everything he did. Similar to composer/pianist/conductors of the past, his active performance life stood in the way of a greater output as a composer. Now that he is no longer with us, we lament that Bernstein perhaps gave too much of his time to live performance and did not leave more behind as a composer. Inasmuch, Bernstein’s creative output echoed the experience of Gustav Mahler who is viewed to have given so much of himself to his time and place as a performer and not having been generous enough to the canon.

I have always found that this point of view devalues what any artist achieves in his or her lifetimes as performers. Arguably, such an attitude makes too much of the importance of recording and composition. Who could possibly place a value on an amazing experience for those who were there in that moment when Mahler conducted an incredibly Tristan und Isolde or when Bernstein brought his unique an invaluable experience to a performance of Shostakovich in front of the composer himself. Who can weight he importance of such things?

Even for those of us who love recordings, a large majority of the magical musical experiences of life transpire in real-time and happen in the concert hall or the opera house while experiencing live music and not at home alone with headphones on. This will always be an issue with music because of its ephemeral nature.

More important to this issue is how creative composers like Bernstein and Glass are actively informed by all their experiences. The great inaccuracy is that we see these kinds of gifted composers as having had to make some sort of choice: a valuation of now versus then. A choice of whether to invest time in leaving something for future audiences or serving the present day. In having spent a lot of time around creative people, that kind of perspective appears to me to be mostly wrong. Artists are compelled by their creative spirit to engage with the most enticing possibility in front of them at any given time. It’s rare and/or generally futile for artists to spend their creative life trying to engineer and promote how they will be viewed in future lifetimes. In other words, while the music they create can time travel and endure for hundreds of years, artists themselves belong to their time and place. They are products of their time and place and their creativity is fueled by that world. At least that’s the case with Glass and Bernstein. More than half a century after some of his greatest works were composed, including the Serenade that was composed in 1954, the predominant theme in Bernstein’s work that emerged is his addressing a crisis of faith in humanity. This theme appeared early in works like his First Symphony and was consistent through works like Mass. Bernstein was clearly reacting to the world around him.

The same can be said of Glass, whose strongest theme through his operas and some art films has been about social transformation. This very big topic has inspired some of Glass’s works. When the Violin Concerto arrived in 1987, as a piece with no programmatic or literary connections, in the mold of a true piece of “classical” music it was conspicuous by it being unlike anything else in the composers catalogue at that point. Now years later we see an incredibly huge body of work that Glass has built up. So when we see the violin concerto in the context of the time, we see the very personal motivations behind its composition. While Bernstein’s Serenade is a kind of musical description of Plato’s investigation of “the nature and purpose of love,” we can see that love was the purpose behind the Glass concerto as well.

Bernstien provided listeners with “guideposts” for listening to his piece on love:

“I. Phaedrus; Pausanias (Lento; Allegro marcato). Phaedrus opens the symposium with a lyrical oration in praise of Eros, the god of love. (Fugato, begun by the solo violin.) Pausanias continues by describing the duality of the lover as compared with the beloved. This is expressed in a classical sonata-allegro, based on the material of the opening fugato.

[The second theme of this sonata movement incorporates disjunct grace-note figures and dissonant intervals in the elegant solo violin part.]

- Aristophanes(Allegretto). Aristophanes does not play the role of clown in this dialogue, but instead that of the bedtime-storyteller, invoking the fairy-tale mythology of love. The atmosphere is one of quiet charm.

[Aristophanes sees love as satisfying a basic human need. Much of the musical material derives from the grace-note theme of the first movement. The middle section of this movement incorporates a melody for the lower strings (marked “singing”) played in close canon.]

III. Eryximachus (Presto). The physician speaks of bodily harmony as a scientific model for the workings of love-patterns. This is an extremely short fugato-scherzo, born of a blend of mystery and humor.

[This section contains music that corresponds thematically to the canon of the previous movement, Aristophanes]

- Agathon(Adagio). Perhaps the most moving speech of the dialogue, Agathon’s panegyric embraces all aspects of love’s powers, charms and functions. This movement is a simple three-part song.

- Socrates; Alcibiades(Molto tenuto; Allegro molto vivace). Socrates describes his visit to the seer Diotima, quoting her speech on the demonology of love. Love as a daemon is Socrates’ image for the profundity of love; and his seniority adds to the feeling of didactic soberness in an otherwise pleasant and convivial after-dinner discussion. This is a slow introduction of greater weight than any of the preceding movements, and serves as a highly developed reprise of the middle section of the Agathon movement, thus suggesting a hidden sonata-form. The famous interruption by Alcibiades and his band of drunken revelers ushers in the Allegro, which is an extended rondo ranging in spirit from agitation through jig-like dance music to joyful celebration. If there is a hint of jazz in the celebration, I hope it will not be taken as anachronistic Greek party-music, but rather the natural expression of a contemporary American composer imbued with the spirit of that timeless dinner party.

Both these composers composed their pieces with an audience in mind. Bernstein’s piece premiered with Isaac Stern at La Scala and the composer anticipated a negative reaction from the Italian press. Glass’s concerto was written for his father who had passed away a number of years before. As a child, Glass had worked for years in his father’s record store. Ben Glass was a untrained music lover. Knowing his father loved the great concertos of Mendelssohn, Tchaikovsky and the like, quite simply Philip Glass composed a piece which his father would have liked. This has been misconstrued a number of times that these masterpieces of the concerto repertoire became the model and inspiration for Glass. That is actually incorrect. In fact, Glass originally planned the piece to be in five short movements, not dissimilar from the layout of the Bernstein concerto. However, the piece evolved over its composition including a key change to have the violin sound better – a decision made with the violinist Paul Zukofsky – and after the first two movements were written it was decided, as a matter of length, to compose third and final movement and avoid an overly long 40 or 50 minute concerto. So its resemblance to historical antecedents was coincidental more than anything else. More than anything else, the final form and content of the Violin Concerto was designed for the pleasure of a single listener, Ben Glass, someone who would in fact never have a chance to hear the piece.

It’s at this point where Glass and Bernstein coincide. A large part of Glass’s artistic formation was to close the gap between idealized future audiences and those of the current day. To Glass, art music of his day was trapped in old ideas, outdated notions about purity, high and low culture, and quality in music being above the intellect of normal people, the great unwashed masses, and true appreciation for music was effectively held for ransom some small German town.

While Bernstein certainly worked to be a popular composer and held audiences in high esteem, Glass’s generation of artists and composers specifically reacted to a breaking point between the official music of the time and they liberated themselves from the lineage of that past in this way. The composers of the mid-1960s reengaged with audiences, rewrote the rules of evaluating creativity of all kinds, and they benefitted ultimately by becoming a coherent and legitimate artistic movement, Minimalism, which could confront the establishment its own terms.

While Glass did not seem to worry himself with the idea of posterity, neither did Bernstein for much of his life (latter-day projects like his operatically recorded West Side Story not withstanding.) Glass and Bernstein were writing for audiences of their time, as they themselves are artists of their time more than anything like musical compatriots. To focus on their similarity these two composers are creative geniuses with an insatiable desire to do it all. Bernstein had a facility that permitted him to excel in whatever he was doing as a composer, a writer, a virtuoso pianist, a communicator and as a composer. Bernstein was quite literally a brilliant creative force while maintaining values based in populism. Much more of a full-time composer than Bernstein ever was, nonetheless Glass has committed many months of every year for half a century to live performance as both a pianist (playing almost exclusively his own music) and with his group The Philip Glass Ensemble. Oddly, it’s only come to be the perception that Glass is a populist once his audience had reached a critical mass. Before that, Glass was exclusively known as an enfant terrible/avant garde composer. Despite the early rejection of his music, the world eventually caught up to him to the point where he was eventually criticized for being too popular to be any good. But that’s another story.

While both men had concurrent lives as performers, and while both composers generally had a populist bent in their personalities, another commonality that we can see in their work is towards the theatrical. Much of Bernstein’s music can be labeled theatrical or programmatic in much the same was as can Glass’s. All three of Bernstein’s symphonies possess extra-musical connections. In his eleven numbered symphonies, Glass has quite a few who venture “dangerously” close to forms like ballet, oratorio, or program music. In the case of the two pieces on this recording of two violin concertos, we can see how both composers dealt with the challenge of writing for violin and orchestra.

For Glass, his Violin Concerto is a piece that exploded within tight formal procedure. This was a marvelous and very powerful part of Glass’s creative life. The novelty and innovation in this concerto springs from use of the violin and orchestra as an expressive medium for his very recognizable musical voice. For a lengthy and useful discussion of the composition of this concerto, it’s of great benefit to refer to Robert Maycock’s book Glass: A Portrait in which Maycock describes the evolution of the piece. For me, what is most interesting is after nearly two decades away from the orchestra, preferring instead to write for the Philip Glass Ensemble while developing his own sound, Glass returned to the orchestra as a possible mouthpiece for his musical voice.

Davies recollects: “I remember doing the premiere (Paul Zukovsky and the American Composers Orchestra). It was I’m quite sure an ACO Commission, Philip was getting comfortable with a classical orchestra after his successes with his early operas and he had a sound and orchestral color in his ear. But the challenge of balancing a large orchestra with a Violin solo was difficult for him (why shouldn’t it be-Brahms couldn’t really handle it either.) And while I had done really successful opera premieres with him, the mutual trust and confidence in each other’s judgment that we have built up over the past 30 years wasn’t yet fully established and Paul, the orchestra, Philip, and I struggled to find a way to play it.”

Maycock goes into lengthy discussion about Glass’s process. What Davies describes above, issues of balance, are at the crux of writing any kind of concerto. Composer John Adams, as he does with his operas, often simply amplifies the solo instrument or voice to achieve his own artistic goal and avoid the issue of balance almost all together. For concert-goers, who might only know any of the famous concertos from recordings, are often underwhelmed in live performance to hear the tiny sound of a of a soloist in pieces like the Tchaikovsky concerto and how often the soloist is drowned out by a Romantic-sized orchestra.

Both of the concertos on this album are performed very often. Glass’s concerto is now three decades old and of all his concert works it is the closest thing he has to an official entry into the canon. For that distinction is thanks largely to Gidon Kremer who lobbied orchestras to perform the piece in the early 1990s when it was new but he was often turned away by orchestras. Kremer’s devotion to the piece manifested itself with the recording Kremer made for Deutsche Grammophon with von Dohnanyi and the Vienna Philharmonic (though the orchestra never performed the piece in concert.) In 2009, Davies and Kremer reunited to perform the piece at the BBC Proms at Royal Albert Hall. This recording featuring virtuoso Renaud Capuçon is the fourth recording on record yet the first with its original conductor Davies who has performed it numerous times since its premiere.

In 2009, I discussed the work with Glass who was at the Albert Hall performance. At that point, Glass said “Davies is the only one to observe my tempo marking in the second movement.” Indeed, in this interpretation with the brilliant Capuçon as soloist, the second movement comes in at over twelve minutes in length as opposed to the usual 8 or 9 minute interpretation. Additionally, Davies commented on the alterations that he has made to the original orchestration – not changing anything but doing some judicious pruning to help the violin be heard above the big orchestra.

Davies elucidates, “The Carnegie performance was still successful with the public, the west coast premiere with Paul at the Cabrillo Festival a couple of years later was a triumph and my confidence and familiarity with the piece grew over the years after additional performances with Gidon Kremer. When Renaud Capuçon and I planned to tour and record the concerto with the Bruckner Orchestra Linz (in 2009, later re-recorded in 2012), Philip have me a green light to basically rework the orchestration which I did extensively-thinning here, alternating unisons and combinations there-to emphasize the structure of the piece and give the violin space acoustically to be always present and when necessary dominate as a solo voice. This recording is the first of this new authorized version. I’m pleased that my first recording of this seminal work, having premiered it so many years ago, is this one with Renaud.”

On interacting with Bernstein, Davies continued, “I had one intense working period with Lenny-as Music Director for the 1989 Beethoven Fest in Bonn. I invited him to be Composer-in-Residence and conducted several of his major concert pieces with the Beethovenhalle Orchestra, while he led a series of concerts with the Vienna Philharmonic. Intense days and late nights, and to this day I value the experiences and memory of this strong musical personality which is clearly heard in his music. I wish he had written more, but I’m grateful for what we have.”

January 31, 2017 marked Philip Glass’s 80th birthday with the world premiere performance of Symphony No.11 at Carnegie Hall almost exactly thirty years after premiering the Violin Concerto, the manuscript of which hangs on the wall at Carnegie, the most famous temple for music in America.

-Richard Guérin, Salem, MA 2016

Publishers (Glass): G. Schirmer, Inc. (ASCAP) o/b/o Dunvagen Music Publishers, Inc.

© 2017 Orange Mountain Music

Listen

Related

COMPOSITIONS:

Concerto for Violin and Orchestra

Violin Concerto No. 1 (2020)

Summary

Music by Philip Glass

David Nebel, violin

London Symphony Orchestra

Kristjan Järvi, conductor

Catalog

Sony Classical

2020

Tracks

Glass Violin Concerto No.1

1. Movement I (6:31)

2. Movement II (10:51)

3. Movement III (10:19)

Stravinsky Violin Concerto

4. I. Toccata (5:03)

5. II. Aria I (4:51)

6. III. Aria II (4:34)

7. IV. Capriccio (5:37)

Listen

Related

COMPOSITIONS:

Concerto for Violin and Orchestra

Violin Concerto No. 1 (2000)

Summary

Music by Philip Glass

Ulster Orchestra

Adele Anthony, violin

Takuo Yuasa, conductor

Catalog

Naxos

2000

Tracks

COMPANY

1. I 2:33

2. II 1:56

3. III 1:50

4. IV 2:41

VIOLIN CONCERTO

5. I 6:51

6. II 8:32

7. III 9:28

AKHNATEN

8. Prelude 12:16

9. Dance (Act II Scene III) 5:34

Credits

Music by Philip Glass. Performers: Adele Anthony, Violin. Ulster Orchestra. Takuo Yuasa, Conductor.

Recorded at Ulster Hall, Belfast, Northern Ireland from 19th to 21st May, 1999. Producer and Engineer: Tim Handley.

Cover Painting: Cendres Bleues 1987 by Tim Smith.

Publisher: Dunvagen Music Publishers, Inc. NY.

© 2000 HNH International Ltd.

Notes

Born in Chicago in 1937 to Jewish immigrant parents, the American composer Philip Glass began his musical studies on the flute and violin, going on to study with Steve Reich at the Juilliard School in New York, and later with Darius Milhaud in Aspen and Nadia Boulanger in Paris. By the 1980s Glass had already made a considerable reputation for himself in the field of composition now generally referred to as minimalism. In his output from the mid-1960s onwards, he had examined the possibilities inherent in subjecting very small amounts of musical material — often just a few notes — to extensive repetition, in a style having some similarities to those of his compatriots and almost exact contemporaries, who include Terry Riley and Steve Reich. For a decade Glass’s concern lay, like Reich’s (the two composers were friends for some of this time), in the audibility of the musical processes — in particular the rhythmic processes — generated by this approach. From 1968, all his compositions were written for the amplified group consisting mainly of flutes, saxophones, electric keyboards and, later, voices that became the Philip Glass Ensemble. In the mid-1970s, however, his interest in the structural rigours of his music lessened, and he began to reinvest melody and harmony — elements which had been sidelined in the obsession with minimalist processes — with a new purchase on their potential. Tunes and the sorts of chord progressions which accompanied them in more familiar kinds of Western music could now be explored afresh in the surviving context of minimalist repetition.

The result was a rather different kind of music from compositions such as Music in Similar Motion of 1969, or even Glass’s first stage work, Einstein on the Beach, conceived in collaboration with the director and designer Robert Wilson and premièred in 1976. New investigations of melody and, especially, harmonic progression were already important strategies enabling Glass to sustain musical and dramatic interest over the several unbroken hours of Einstein’s duration. But it was only when these had been allied with the vocal and orchestral forces of the traditional Western opera house — forces much more conventional than those of the composer’s own ensemble — that he was able to fulfil his new lyric and dramatic aspirations with the resources which come as part of the natural territory of twentieth-century opera. This new approach — partly a matter of text as well as texture (the voices of the early Philip Glass Ensemble did not sing texts as such, only individual syllables or numbers) — could also be tested on more rock-orientated endeavours. What Glass’s music in the last quarter of a century has lost in note-to-note rigour, it has gained in range of expression.

While the differences between Glass’s early minimalist and later (post-?) minimalist scores are considerable — making possible not only a greater range but also, as a consequence of this, the composer’s considerable success since the early 1980s continuities between the old Glass and the new abound. One of these is his involvement with writing music for the ‘legitimate’, rather than the musical, theatre. The composer’s first wife, JoAnne Akalaitis, had been much involved with a theatre group first formed during the couple’s years in Paris in 1964-6, which back in New York eventually became known as Mabou Mines. This group became particularly associated not only with the plays but also with other writings of Samuel Beckett, of which the author allowed Mabou Mines to make staged versions.

Company originated as instrumental music for Fred Neumann’s adaptation of Beckett’s prose text of the same name, mounted in New York in January 1983; it was thus composed around the same time as Akhnaten. Like this opera, Glass’s Company is steeped in doom-laden arpeggios in minor keys cross-cut with driving rhythms: features shared, in fact, by all three compositions on this disc. Beckett’s Company concerned, as so often with this author, with memory, but unusually autobiographical — involves a solitary figure lying on his back in the dark: the music’s dark ruminations thus seem entirely appropriate. As a concert piece, the four short movements taken from this score can be performed either by a string quartet (it is also known as Glass’s Second String Quartet) or, as here, by a string orchestra.

Akhnaten, first performed in Stuttgart on 24th March 1984, is the composer’s third large-scale stage work; it was conceived as the final instalment of a trilogy with Einstein and Satyagraha (1980), the latter, based on Mahatma Gandhi’s early years in South Africa, being Glass’s first opera for the forces of the conventional Western opera house. Akhnaten’s subject is the Egyptian pharaoh of the fourteenth century BC who is held to be the first monotheist and whose radicalism led, after seventeen turbulent years, to his overthrow and presumed murder. The opera’s three acts show the rise and fall of Akhnaten in a series of tableaux; the libretto is sung in a mixture of ancient languages and English.

On the present recording, the opening Prelude with its magnificently sustained arc of tension and not-quite release — is followed by the Dance from Act Two, Scene 3 which, in more obviously rhythmic fashion, celebrates the inauguration of the city of Akhetaten created by the new pharaoh; in an actual production, musicians appear on stage along with the rest of the cast. In both these extracts, some unsettling metrical ambiguities enhance the drama. And throughout the opera, the predominatingly dark mood is enhanced by the absence of violins from the orchestra (an omission actually brought about by practical restrictions on the Stuttgart première performances).

The Violin Concerto is the first of many orchestral works that Glass has composed on commission since the late 1980s, following the acclaim accorded to Satyagraha and Akhnaten. The choice of the concerto form seemed a natural one for a composer then currently obsessed with opera: he found it ‘more theatrical and more personal’ than music for orchestra alone. The work was premièred by Paul Zukofsky and the American Composers Orchestra under Dennis Russell Davies in New York on 5th April 1987. Both these musicians had worked with Glass before: Zukofsky played the part of Albert Einstein (in Einstein on the Beach the character is represented by a solo violinist, not a singer) in that stage work’s first performances; Davies had conducted the première of Akhnaten.

The concerto’s familiar three-movement, broadly fast-slow-fast, layout was in fact accidental. Zukofsky, who collaborated closely with the composer during the work’s gestation, had requested a slow, high finale. Glass’s original plan to have five short movements changed in the course of composing the piece, and he ended up with two movements followed by a third one which concludes with a slow coda making references to the material of both previous movements, thus also complying with his soloist’s wishes.

The composer’s familiar repeated arpeggiations, together with other types of figuration likewise idiomatic meat and drink to the fiddle, sometimes predominate over the melodic impulse. Yet this choice of solo instrument has also inspired lyrical material, intercut with and sometimes counterpointing the arpeggiations in quite dramatic fashion in the first movement. The central movement’s set of variations on a descending bass line, too, allows the solo part to soar and the variations themselves to rise and fall in a simple but moving progression, while the coda to the finale brings another quite dramatic movement, and the work as a whole, to a rapt conclusion. The affecting minor modes and chromatically shifting harmonies of the Violin Concerto are entirely typical of Glass’s style at the time it was composed.

— Keith Potter

NOTES ABOUT The players

Adele Anthony. Winner of the First Prize in the 1996 Carl Nielsen International Violin Competition in Denmark, Adele Anthony made her earlier debut in 1983 with the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra and subsequently appeared as a soloist with all six symphony orchestras of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and with orchestras in New Zealand. Her career has also brought performances with leading orchestras and collaboration with distinguished conductors throughout Europe. Adele Anthony began violin lessons at the age of two in Tasmania and studied with Beryl Kimber as an Elder Conservatorium Scholar at the University of Adelaide until 1987. She later worked with Dorothy DeLay, Felix Galimir and Hyo Kang at the Juilliard School in New York, where she held a number of scholarships and awards. A series of competition triumphs include early victory in the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Instrumental and Vocal Competition and in the 1992 Aspen Walton Competition, and prizes in the 1993 Jacques Thibaud Competition in Paris and the 1994 Hanover International Violin Competition. Her recordings include a 1998 release of music by Schubert for Naxos, in addition to recordings for other labels. Adele Anthony plays a 1735 Guarneri del Gesù violin on extended loan to her from Clement Arrison, through The Stradivari Society in Chicago.

Ulster Orchestra. Based in Belfast, Northern Ireland, the Ulster Orchestra was formed in 1966 and has established itself as one of the major symphony orchestras in the United Kingdom. The orchestra’s varied activities include participation in the Belfast Festival at Queen’s and the Belfast Proms, accompaniment to Opera Northern Ireland, educational work and concerts throughout Northern Ireland. The internationally acclaimed Dmitry Sitkovetsky is the orchestra’s Principal Conductor and Artistic Advisor, while Takuo Yuasa is Principal Guest Conductor. The orchestra records and broadcasts extensively for the BBC and has acquired a high profile through its frequent television appearances. In January 1997 the orchestra gave the first public performance at Belfast’s new major performance venue, the Waterfront Hall. This concert preceded the broadcast on network television of the orchestra’s performance at the official opening concert together with Dame Kiri Te Kanawa, in the presence of HRH the Prince of Wales. The Ulster Orchestra has made over fifty commercial recordings, several of which have received prestigious British awards. Successful tours of Europe, Asia and America have added to the growing international reputation of the orchestra, as have its regular appearances at the BBC Henry Wood Promenade Concerts.

Takuo Yuasa. The highly regarded Japanese conductor Takuo Yuasa has held positions as Principal Conductor of the Gumma Symphony Orchestra in Japan, Principal Guest Conductor of the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra and his current position as Principal Guest Conductor of the Ulster Orchestra in Belfast has been extended until 2002. He conducts extensively throughout the Far East, Australia and Europe.

Takuo Yuasa was born in Osaka where he studied piano, cello, flute and clarinet from an early age. At eighteen he left Japan to study in the USA at the University of Cincinnati where he completed a Bachelor Degree in Theory and Composition. He later moved to Europe to study conducting with Igor Markevitch, with Hans Swarowsky at the Hochschule in Vienna and with Franco Ferrara in Siena. Later he became assistant to Lovro von Matacic, working with him in Monte Carlo, Milan and Vienna.

Listen

Related

COMPOSITIONS:

Concerto for Violin and Orchestra

Violin Concerto No. 1 (1999)

Summary

Music by Philip Glass / John Adams

Houston Symphony

Robert McDuffie, violin

Christoph Eschenbach, conductor

Catalog

Telarc

1999

Tracks

JOHN ADAMS: Violin Concerto

1. I 14:44

2. II. Chaconne: Body through which the dream flows 11:02

3. III. Toccare 7:45

PHILIP GLASS: Concerto for Violin and Orchestra

1. I 6:25

2. II 9:53

3. III 9:46

Credits

Violin concertos of John Adams & Philip Glass. Robert McDuffie, Violin. Christoph Eschenbach conducts Houston Symphony.

Recording Producer: Erica Brenner. Recording Engineer: Jack Renner. Executive Producer: Robert Woods.

Technical Assistants: Robert Friedrich, Marlan Barry, Shannon Smith.

Production Assistant: Thomas C. Moore.

Editor: Rosalind Ilett.

Recorded in Jones Hall, Houston, Texas, September 28-29, 1998.

Microphones: Neumann M50b; Schoeps CMC-6 / MK-2, MK-3; Neumann KU-100.

On-Stage Microphone Preamplifiers: Millennia Media HV-3 Quad. Console: Ramsa WR-S4424S, custom engineered by John Windt. Interconnecting Cables: This recording utilized the latest in cable technology including Monster Cable M1500, M1.5, Series I & III Prolink and Music Interface Technologies Proline with Balanced Line Terminators. Digital Recording Processor: Telarc/Ultra-Analog Tandem 20-bit ADC custom engineered by Dr. Thomas Stockham, Gary Gomes, and Kenneth Hamann. Monitored through Krell “Studio” 20-bit DAC. Power Amplifier: Threshold SA-4. Monitor Speakers: ADS 1530. Control Room Acoustic Treatment: sonex by illbruck usa. Digital Editor: SADiE Disk Editor. 20-to 16-bit Encoding: Apogee UV-1000 Super CD Encoder.

Cover Illustration: Paul Klee. Paul Klee, “Doppelzelt / Double Tent,” 1923, 114; 50.6×31.8 cm; water— color and pencil on paper;. Private Collection.

© 1999 VG Bild Kunst Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Art Director and Cover Design: Anilda Carrasquillo.

Publishers (Adams): Boosey & Hawkes, Inc. (ASCAP). Publishers (Glass): G. Schirmer, Inc. (ASCAP).

© 1999 Telarc

Notes

“You know there is a maverick tradition in American music that is very strong. It’s in Ives, Ruggles. Cage, Partch, Moondog, all of these weird guys. That’s my tradition.” Thus Philip Glass traced his artistic lineage in an interview with the composer Robert Ashley. Glass, born in Baltimore on January 31, 1937, began his musical career in a conventional enough manner: study at the University of Chicago and Juilliard; a summer at the Aspen Music Festival with Milhaud; lessons with Nadia Boulanger in France on a Fulbright scholarship; many compositions, several of them published, in a neoclassical style indebted to Copland and Hindemith. In 1965, however, Glass worked with the Indian sitarist Ravi Shankar in Paris on the score for a film titled Chappaqua, and that exposure to non-Western music was the turning point in forming Glass’ mature style.

In 1965-1966, Glass spent six months traveling in India, North Africa, and Central Asia, and he returned to New York in the spring of 1966 with a new musical vision (and a new religion — he has been a Tibetan Buddhist for years). Glass rejected his earlier works, formed an ensemble of amplified flutes and saxophones, electric organs and synthesizers, and began writing what is commonly known as “Minimalist” music (though Glass loathes the term; Debussy likewise insisted that he was not an “Impressionist.”) “Minimalist” music is based upon the repetition of slowly changing common chords in steady rhythms, often overlaid with a lyrical melody in long, arching phrases. Glass views this style, which contrasts starkly with the fragmented, ametric, harshly dissonant post-Schoenberg music that had been the dominant style for the twenty-five years after the Second World War, as hypnotic and trance-like, lifting the spirit out of the mundane and freeing the mind. Minimalist music is meant, quite simply, to sound beautiful and to be immediately accessible to all listeners. Indeed, Glass represents the epitome of the modern “cross-over” artist, whose music appeals equally to classical, rock and jazz audiences.

Such an extraordinary, new style was not quickly accepted, but Glass was determined to continue on the path he had chosen. He kept composing and honing the skills and performances of his ensemble, but supported himself for some time as a taxi driver and plumber. His first wide recognition came with the four-and-a-half-hour opera Einstein on the Beach, produced at the Metropolitan Opera House on November 21, 1976, in collaboration with multi-media artist Robert Wilson. Glass has since produced several more operas (including Satyagraha, based on Gandhi’s years in South Africa; Akhnaten, concerning an Egyptian pharaoh martyred for his monotheism; and The Voyage, commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera and premiered there in 1992), compositions for dance companies, film scores (perhaps most memorably those for The Thin Blue Line and Koyaanisqatsi, an extraordinary movie comprising exclusively images and music without a single spoken word), works for his own ensemble (its 1981 recording, Glassworks, was a best-seller), and several unclassifiable theater pieces (The Photographer, 1000 Airplanes on the Roof, The Mysteries, and What’s So Funny?). Among his recently completed works are Low Symphony (based on David Bowie’s album Low), Second Symphony (commissioned by the Brooklyn Philharmonic), three pieces based on the films of Jean Cocteau (Orphée, La Belle et La Bête, and Les Enfants Terribles), The Witches of Venice (a ballet created by Beni Montressor and commissioned by Teatro alla Scala, Milan), and the Symphony No. 3 for the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra.

Glass composed his Violin Concerto, his first orchestral work since his student days, between November 1986 and February 1987 on commission from the American Composers Orchestra, which gave the work’s premiere at New York’s Carnegie Hall under the baton of Dennis Russell Davies on April 5, 1987, with the composer’s long-time friend and collaborator Paul Zukofsky as soloist. Though the work is scored for standard orchestra without the electronics that give a characteristic sonority to so many of Glass’ compositions, he said that “the piece explores what an orchestra can do for me. In it, I’m more interested in my own sound than in the capability of particular orchestral instruments. It is tailored to my musical needs.” The Concerto’s form evolved as Glass worked with its musical ideas (“the material finds it own voice,” he explained), and finally settled into a conventional three-movement fast-slow-fast arrangement with a reflective coda added at the end. Glass sees the genre of the concerto as “more theatrical and more personal” than the purely orchestral forms, and the soloist in this work finds an individuality that sets it apart from the larger ensemble, sometimes strewing lightning-flash cascades of arpeggios upon the pulsing background chords, sometimes soaring over them with spacious, arching, cantabile lines.

— Richard E. Rodda

Listen

Related

COMPOSITIONS:

Concerto for Violin and Orchestra

Violin Concerto No. 1 (1993)

Summary

Music by Philip Glass / Alfred Schnittke

Vienna Philharmonic

Gidon Kremer, violin

Christoph von Dohnányi, conductor

Catalog

Deutsche Grammophon

1999

Tracks

PHILIP GLASS: CONCERTO FOR VIOLIN AND ORCHESTRA

1. I 6:38

2. II 8:46

3. III 9:30

ALFRED SCHNITTKE: CONCERTO GROSSO NO. 5

4. Allegretto 7:46

5. (Without tempo indication) 5:19

6. Allegro vivace 6:02

7. Lento 8:28

Credits

Concerto for Violin and Orchestra: Music by Philip Glass. For Paul Zukofsky and Dennis Russell Davies. Commissioned by The American Composers Orchestra, Inc. Gidon Kremer, Violin. Vienna Philharmonic. Christoph von Dohnányi, Conductor

Concerto Grosso No. 5 for Violin, an Invisible Piano and Orchestra: Music by Alfred Schnittke. Gidon Kremer, Violin. Rainer Keuschnig, Piano. Vienna Philharmonic. Christoph von Dohnányi, Conductor

Recordings: Vienna, Musikverein, Grosser Saal, 11/1991 (Schnittke) & 2/1992 (Glass). Produced by Wolfgang Stengel. Balance Engineer: Rainer Maillard. Editing: Ingmar Haas (Glass). Recorded using B & W Loudspeakers.

Publishers: Glass © 1987 Dunvagen Music Publishers, Inc. (ASCAP); Musikverlag Hans Sikorski, Hamburg (Schnittke). For Philip Glass: Music: Music Sales Corp. / G. Schirmer, Inc. Recordings: Euphorbia Productions Ltd.

© 1993 Susan Feder. Art Director: George Patapow. Cover Photo: Hideki Kuwajima/Photonica. Designer: Gordon H Jee.

© 1993 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH, Hamburg.

Notes

“The search for the unique can lead to strange places. Taboos — the things we’re not supposed to do— are often the more interesting. In my case, musical materials are found among ordinary things, such as sequences and cadences.”

When Philip Glass wrote his first major orchestral work, this 1987 Violin Concerto, his compositional “search” indeed led him to the ordinary. Glass, best known at the time as a composer of music for opera, film, theatre, dance and his own Philip Glass Ensemble, took on one of the most enduring genres in Western art music. In so doing he cast it in most familiar terms.

Glass’s Violin Concerto falls into the three-movement structure common to the vast majority of concertos written in the last three centuries, and is scored — as are his operas— for an orchestra of conventional size and configuration. “I like the normal orchestra,” he commented at the time of the première by the American Composers Orchestra (Dennis Russell Davies conducting and Paul Zukofsky, violin) on 5 April 1987. “I have an alternative electronic medium, which is my ensemble. By writing for both there’s a balance in my activities.”

Familiar, too, are the opening chugging chords, the solo violin’s first arpeggios, and the repetitive patterns that cause time to be absorbed into large units rather than to be divided up: the Concerto is instantly identifiable as music by Philip Glass. “This piece explores what an orchestra can do for me. In it, I’m more interested in my own sound than in the capability of particular orchestral instruments. It is tailored to my musical needs.” Also to his dramatic needs: Glass observed that the concerto form “is more theatrical ond more personal” than pure orchestral music.

Born in Baltimore, Maryland, on 31 January 1937, Glass was on a conventional career path (studies at the University of Chicago, the Juilliard School, and with Nadia Boulanger) when in 1965 he met Ravi Shankar in Paris and worked with him on the film Chappaqua. The collaboration resulted in a radical rethinking on Glass’s part, toward a music structured by repetitive rhythmic patterns.

To explore this new idiom he formed the Philip Glass Ensemble in 1968. Within ten years Glass was writing large-scale operas and theatre pieces that brought him worldwide fame: among them, Einstein on the Beach, Satyagraha, Akhnaten, The Juniper Tree, The Photographer, The Voyage (a Metropolitan Opera commission to celebrate the Columbus quin-centenary in 1992). Glass has also written film scores: Koyaanisqatsi, Powaqqatsi, Mishima and The Thin Blue Line; dance scores for Twyla Tharp, Laura Dean, Lucinda Childs and Molissa Fenley; and, since the Violin Concerto, a number of works for orchestra, including The Light, The Canyon, and Itaipu (for chorus and orchestra). Projects under way in the early 1990s include Orphée, a chamber opera; The Palace of the Arabian Nights, a collaboration with Robert Wilson; and an opera entitled White Raven.

The violonist for whom this Concerto was written, Paul Zukofsky, was a close colleague of Glass’s and had long urged the composer to write a concerto. He collaborated closely with Glass during the composition of the piece, asking, for example, for a slow, high finale. Glass’s plans to comply were thwarted when he found his original conception of a piece in five short movements giving way to a long first and second movement. “The material finds a voice of its own,” he conceded, revealing that the Concerto’s three-movement structure was actually “an accident”. While Glass ultimately wrote a fast thrid movement, its slow coda both satisfied Zukofsky’s request and harkened back to the other two movements. The violinist also offered suggestions in the first movement that had large-scale harmonic implications: “I heard the piece with a ‘tonal identity’ of C minor and D,” recalled Glass, “but by moving it up a step the violin sounds far better.” Glass found their collaboration highly satisfactory: “This is the piece that I wanted to write.” – Susan Felder

Listen

Related

COMPOSITIONS:

Concerto for Violin and Orchestra

Violin Concerto No. 1 (1979)

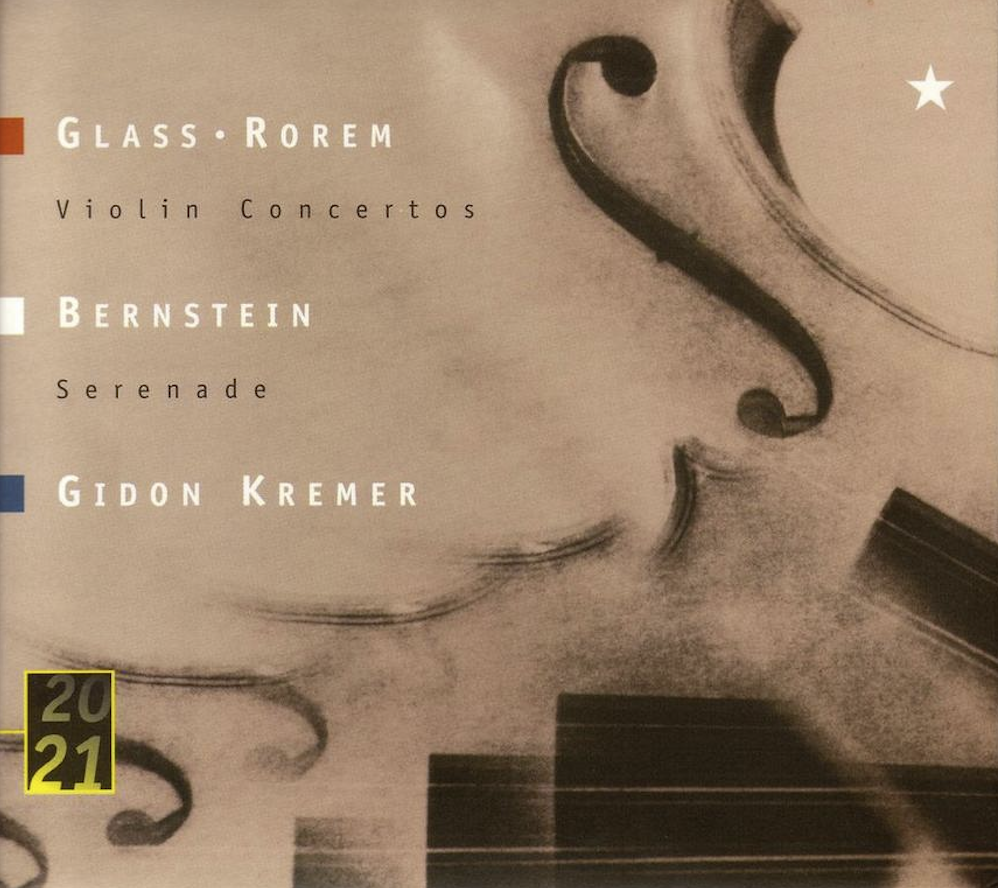

Summary

Music by Philip Glass / Ned Rorem / Leonard Bernstein

Gidon Kremer, solo violin

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Christoph von Dohnanyi

New York Philharmonic, conducted by Leonard Bernstein

Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Leonard Bernstein

Catalog

Deutsche Grammophon

1979

Tracks

1-3 Philip Glass Concerto For Violin And Orchestra

4-9 Ned Rorem Violin Concerto

10-14 Leonard Bernstein Serenade (after Plato’s Symposium) for violin and orchestra

Credits

Music by Philip Glass / Ned Rorem / Leonard Bernstein

Gidon Kremer, solo violin

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Christoph von Dohnanyi

New York Philharmonic, conducted by Leonard Bernstein

Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Leonard Bernstein

Notes

Here are three 20th-century violin concertos written within a 30-year period in three totally different styles, played by a soloist equally at home in all of them. Bernstein’s Serenade, the earliest and most accessible work, takes its inspiration from Plato’s Symposium; its five movements, musical portraits of the banquet’s guests, represent different aspects of love as well as running the gamut of Bernstein’s contrasting compositional styles. Rorem’s concerto sounds wonderful. Its six movements have titles corresponding to their forms or moods; their character ranges from fast, brilliant, explosive to slow, passionate, melodious. Philip Glass’s concerto, despite its conventional three movements and tonal, consonant harmonies, is the most elusive. Written in the “minimalist” style, which for most ordinary listeners is an acquired taste, it is based on repetition of small running figures both for orchestra and soloist, occasionally interrupted by long, high, singing lines in the violin against or above the orchestra’s pulsation. Gidon Kremer, well known for his championship of contemporary composers, plays fabulously; his tone soars, shimmers, and glows. His identification with the music is complete. — Edith Eisler (Amazon.com)

Listen

Related

COMPOSITIONS:

Concerto for Violin and Orchestra