Mickey Lemle: What’s this piece you were just playing?

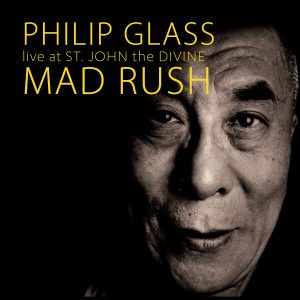

Philip Glass: This is a piece, we now call it Mad Rush, but that wasn’t the original name. This music was written for the evening in 1979, I think it was November, when his Holiness the Dalai Lama gave his first public address in North America.

He was invited to give that here in St. John the Divine, this cathedral. I knew the people from the Tibet House and the Tibet Fund office. I’ve known them for a while and they asked me if I would play some music before he came. They weren’t sure how timely his arrival would be and they knew the place would be full with people. Although in 1979 it was quite different from today. But still there was a big crowd to see it. So I wrote a piece of music. I was living right near here at the time so I came here and composed the music here on this organ.

It was actually an earlier version of this organ. It’s been rebuilt a bit but this is the same organ. I was sitting in this place. I came up and composed this piece on this organ for that event.

Then the next time I wrote music for Kundun. But this piece was really the entrance into that association with him.

ML: At the time in ’79, were you a follower of his?

PG: I had met Rinpoches from his particular tradition in 1967, so it was 12 years after in 1979. So I had some sort of acquaintance and I had been to Dharamshala in ’71 or ’72 and I had met him at that time as well. I knew him as thousands of people who met him his first years in exile, after coming out of Tibet.

Over time he got to know me a bit so that one time when I saw him he said “ah, a familiar face.” We talked a lot. We had a number of conversations about music and the Dharma. He is certainly, a major major figure, in that tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, probably the most important living figure that we have.

I was very fortunate to spend time with him in these ways. Later I got involved with Tibet House and it was something that he invited a number of us to start for him. That would have been Bob Thurman, Richard Gere, a guy named Peter McCray. There were a number of other people. Melissa Mathison was part of it. She eventually wrote the script for Kundun. Elizabeth Avernal was another. There was a small group that started it. So that was another connection. So I had built up all these connections with him. To say I was a follower would be both to understate and to overstate it at the same time.

ML: Can you see in any way that he might have changed in the past 40 years that you’ve known him?

PG: You know it’s interesting that you should ask about that because he has learned more about us than we have of him. He got involved in mind/life study. He met so many people and got used to working with us. I helped with concerts for “Heal the Divide” which Richard Gere organized. Over time, I noticed that he had become familiar with us.

Whether we got that familiar with him I can’t say. I think he learned more about us and he wanted to. What I found was that many of his people who came out of Tibet know they were going to be here for a while. If they get back to Tibet we don’t know. But he took on not just American culture and European culture. He’s been all over the world. He’s become a No.1 world citizen. He’s not the relatively innocent young man who left Tibet in the late 1950s.

He’s probably the most widely recognized person on the planet today. He knows a lot more about what we do and he’s been extremely skillful in both presenting his tradition but also showing an honest and true respect for the traditions he encounters, which was also a lesson in itself.

ML: Are you a practicing Tibetan Buddhist?

PG: I’m a practicing American something or other. I’m not Tibetan, clearly. My family were Jewish but they were the atheist kind of Jews who didn’t do anything. So I’m probably a third generation atheist from that point of view. But I became very interested in the training that was available, over the years since ’67. I’ve been involved in that practice for a long time. I’m not particularly skillful at it. I learned something of the language and one point. I can manage that. As I spent more time with music and less time with that part my language studies deteriorated rapidly but I could write and speak a little bit at one point and that’s been helpful.

ML: Do you have a practice?

PG: Of course I do. But it include so many things. There’s Tai Chi, Qui Gong, and the mind-training that is presented in the Gelugpa tradition of Tibet. It is the one that I know but I have read widely about the other ones I’ve studied the “Life and Times of Milarepa” and other people who are not actually part of this lineage. I haven’t gotten involved in any sectarian attitude about it.

The principle thing that I’ve found is that the training is extremely valuable and useful in living in a world of stress, full of negativity, what we would call evil. Bad things happen. When you live in a world that’s complicated, the training that comes with that tradition (Tibetan Buddhist) is very helpful. The people who spend time with it – not so much myself, I haven’t been that good at it, I’ve known people that did – I can tell you how remarkable it’s been for them. Even in my own limited way it’s been valuable. Without a doubt.

ML: Has your association with your various practices affected your music?

PG: You know it’s an interesting question. In point of fact there’s subject matter which is strictly Tibetan. For example, there’s the film score for Kundun. I’ve set “Songs of Milarepa” to music. I’ve gone a little bit further than that in setting numerous texts by Shantiteva who wrote the celebrated and influential book “The Buddhist Way of Life.” I’ve set a number of verses to music.

It’s not a casual relationship. In a way I felt that these things could be easily understood. The ones that I picked, I picked them because I thought people would like to hear them. I’ve done it with great pleasure.

I’ve talked with His Holiness about this. I really feel a deep connection between mind training and artistic creation. He said, “ I don’t know anything about art.” I said, “You do! Musicians have gurus. We have practice. The actual details may be different but the structure of the life is almost identical.” In any case, I’ not the type of person who would have ended up in a monastery. That wasn’t my temperament.

WE look around and struggle to find elements in our culture which will support us and nourish us. Now, if we think of ourselves as a broader culture, a world culture, you can actually find things. If we stick too close to home we’re not going to do that well.

ML: When you perform, do you feel like you are doing it to serve an audience?

It’s interesting this question about motivation. To tell you the truth, when people say they love the music, in fact that’s not why I play the music. It hardly is why I write music. The thing that compels me to this artistic activity doesn’t have to do with other people.

I was talking with a good friend of mine, Gelek Rimpoche, about this. He was saying that this activity has been very helpful. I wasn’t motivated by that. He says, “It doesn’t matter!” I had thought motivation was everything. But motivations can be layered and can be hidden. I’m not aware of that. Of course I like it when people like the music. I don’t go about my work as if I were a good Samaritan helping the world. I do it to get through my own life and my own difficulties. Most artists will tell you that. They’ll say they do it to keep their sanity. It gets right down to that.

ML. Is part of your quest of composing music to find the transcendent?

PG: Well I think the activity of the artist is about transcending the ordinary world. The world of appearances. However, they are not alone in doing that. I would say anyone who devotes themselves to the well-being of other people automatically does that. They can be teachers or people in healthcare. It can be someone who runs a factory who looks out for the employees and who takes an interest in their well-being. It’s any of these things. Any profession can lead you to that.

For me, I had noticed that (though I’m not a particularly good example) the artistic contribution to the world is a real thing, whatever the motivation might be. My friend Allen Ginsberg had a t-shirt that said:

“While I’m here what shall I do? – You should do the work – What is the work? – To ease the suffering of life.”

It’s beautiful: to ease the suffering. That’s the job of human beings.

The Dalai Lama had given a talk about “the Bhodi Mind.” They asked him, “What are you experience with love?” He said, “When I think about people, animals, and insects.” Insects. That’s a hard one. Very few people think of insects. He thinks of insects! He said, “I am so moved when I think of them that I weep. I’ve been known to weep during my teaching because I’m so active with these things.”

I thought to myself “wow. Insects…boy.” (laughs)

ML. Does your own spiritual work help you find out where music comes from?

PG: No, I’ve never found that out. I have a different idea at this point (pauses.) When people ask me about music and I’ll say “Music is a place,” in the esoteric tradition of Himalayan or Tibetan Buddhism, they talk about the “Pure Land.” I think that music is a pure land. The people who are lucky to spend time in a pure land, if you look at it, that’s what it is. The motivation has something to do with that. So in fact it is a doorway to transcendence.

ML: Is there anything that people should know about His Holiness?

The most important thing is that there’s a trueness to him. A realness that goes right through to the bones. Many of us, we see each other as almost phantoms. We have layers and layers of delusions and self-absorptions. It’s normal. It’s not terrible. It’s rather normal. When I see him, it’s someone who managed to pierce a lot of the shells that some of us have built around ourselves. And he does it in a very simple way. He will tell you. His message is compassion. He’ll sometimes talk about emptiness. Those two together become the basic idea.

He mostly talks about that. He talks from the heart and my impression of him is that what Akhnaten, the 18th Dynasty Pharaoh said, “He walked in truth.” The Dalai Lama, he walks in truth.

1 thought on “An Interview with Philip Glass – Mad Rush & the Dalai Lama”

Comments are closed.